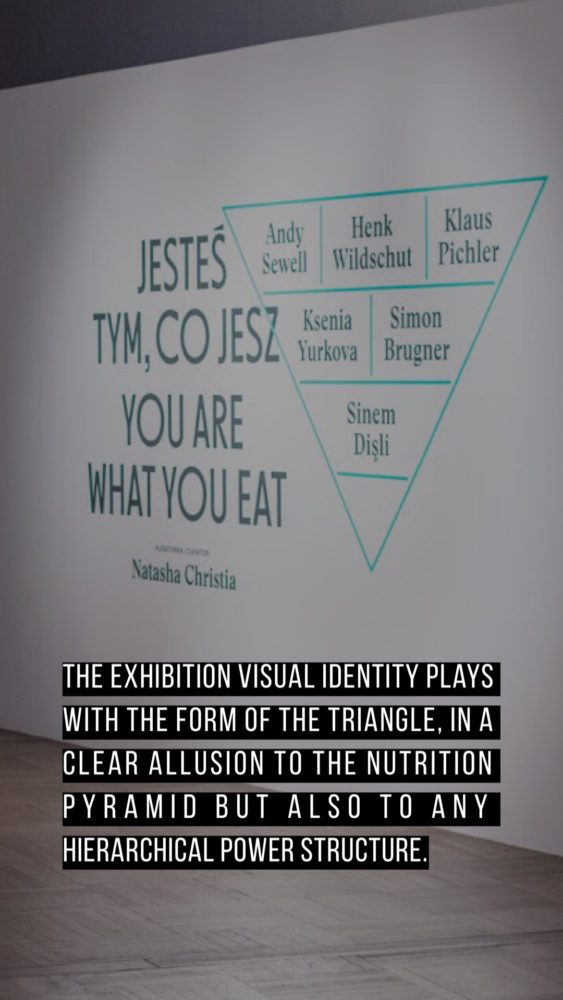

A group exhibition on food, identity politics and ideology, conceived for Krakow Photomonth.Krakow Photomonth

Featuring artists: Sinem Dişli, Andy Sewell, Klaus Pichler, Simon Brugner and Ksenia Yurkova.

Bunkier Stzuki Gallery, Krakow

April 26-June 24, 2019.

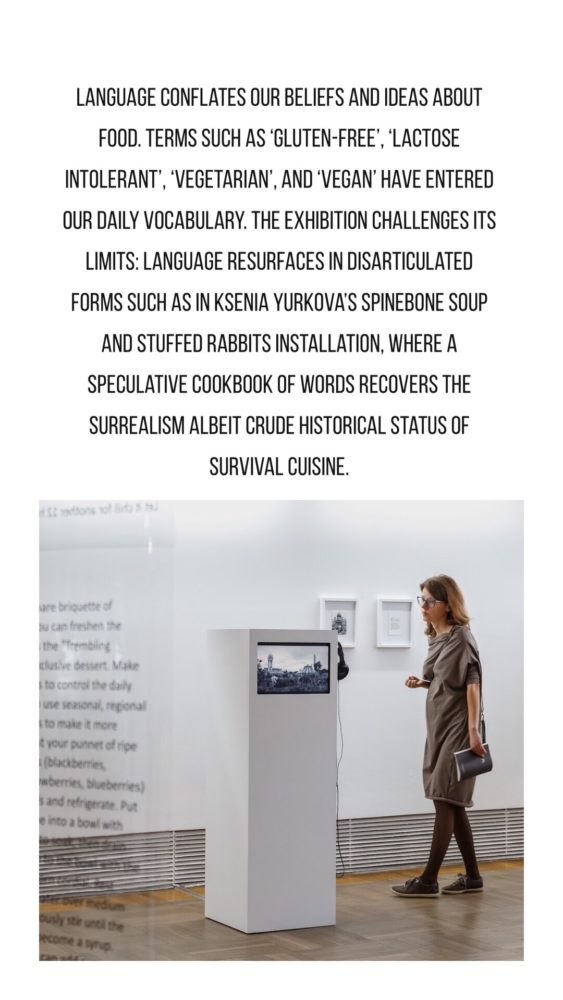

Curatorial statement: Nowadays, perhaps more than ever, our relation to what we produce, eat, and ingest has become increasingly politicised. Food recipes and diet trends have turned into moral status claims, badges of political affiliation, even hopes for redemption. From advertising billboards, cooking blogs, and mouth-watering Instagram pics of elaborately designed dishes, terms such as ‘gluten-free’, ‘lactose intolerant’, ‘vegetarian’, and ‘vegan’ have entered our daily vocabulary. We symbolically savour and allow to ferment identity, language, and ideology through what we eat—or, in many cases, through what we abstain from eating or drinking. And yet, when sitting at the table, we rarely bind our food preferences to global malnutrition, the sins of industrial production, the ongoing controversies over genetic modifications, or the inhumane treatment of animals.

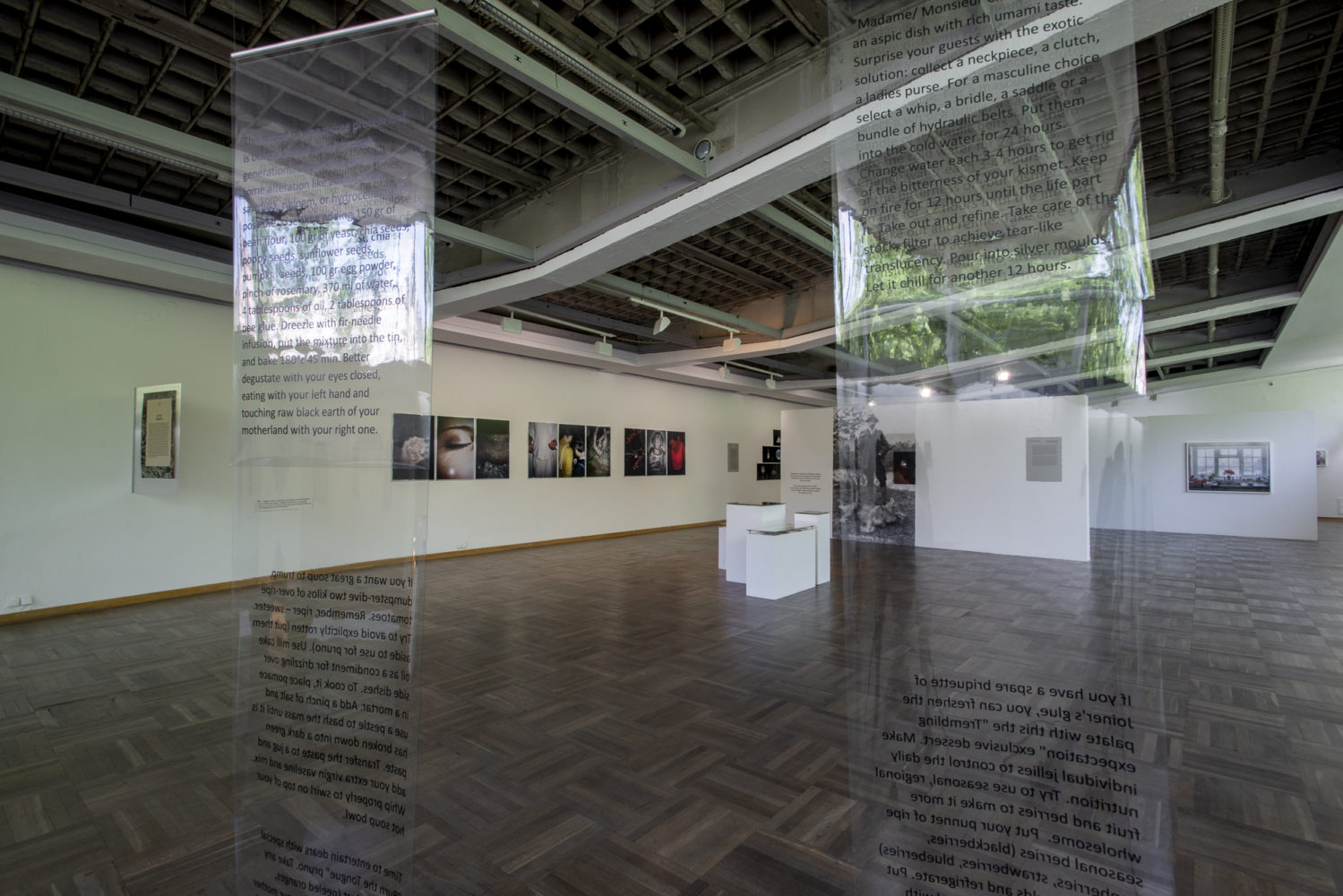

‘You are what you eat’, an aphorism that conceals more than it initially insinuates, lends its name to this group exhibition, which approaches the vast subject of food through the angle of identity politics and ideology. Paraphrasing Claude Lévi-Strauss’ assertion that food must not only be ‘good to eat’ but also to ‘think’,[1] the show is structured around a polyphonic narrative of disassembly. Four texts alongside citations from a handful of sources formulate a series of hypotheses to be questioned within the exhibition space through six contemporary photographic projects on the subject.

Following Michel Foucault’s and Giorgio Agamben’s[2] formulations on biopolitics as arising at the threshold of modernity when natural life begins to be included in the calculations of the State, the body is viewed here as a biopolitical entity inscribed in a nexus of sovereign control. In this context, culinary functions and practices are inevitably linked to processes of identity politicisation.

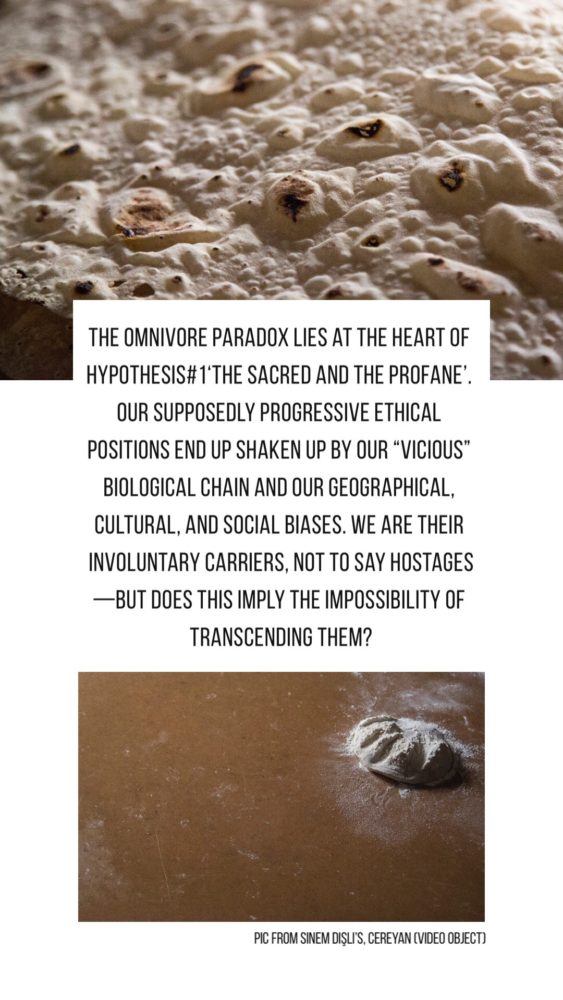

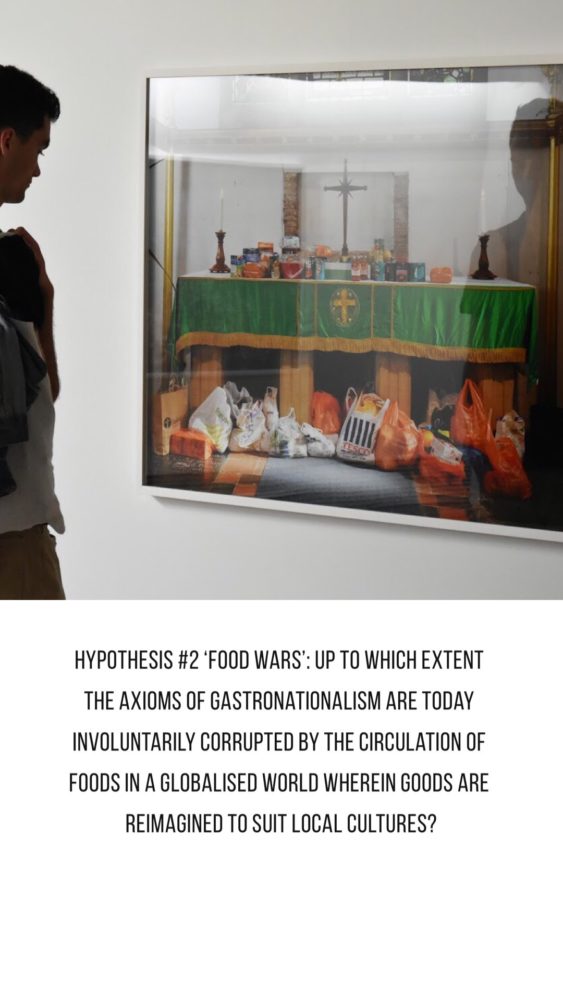

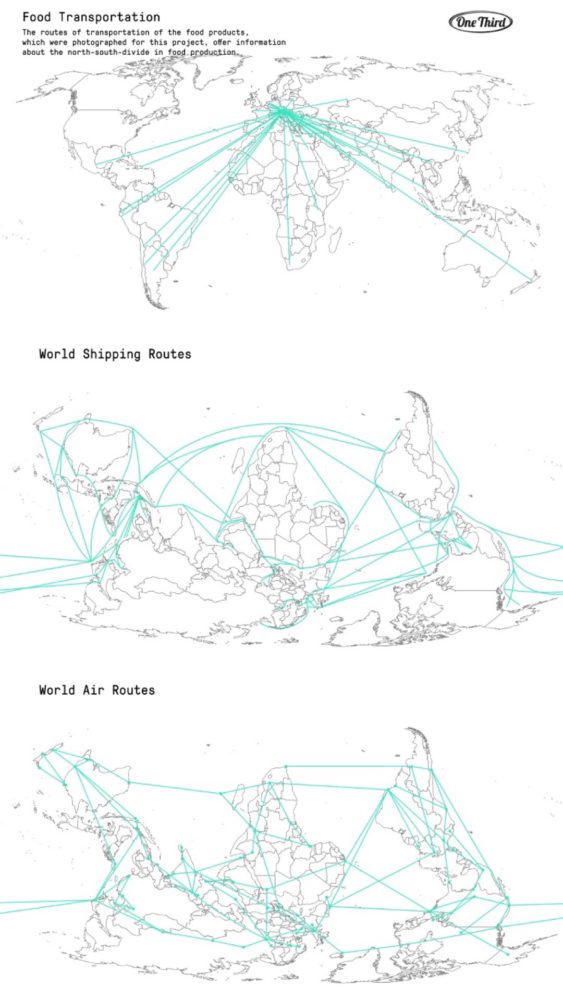

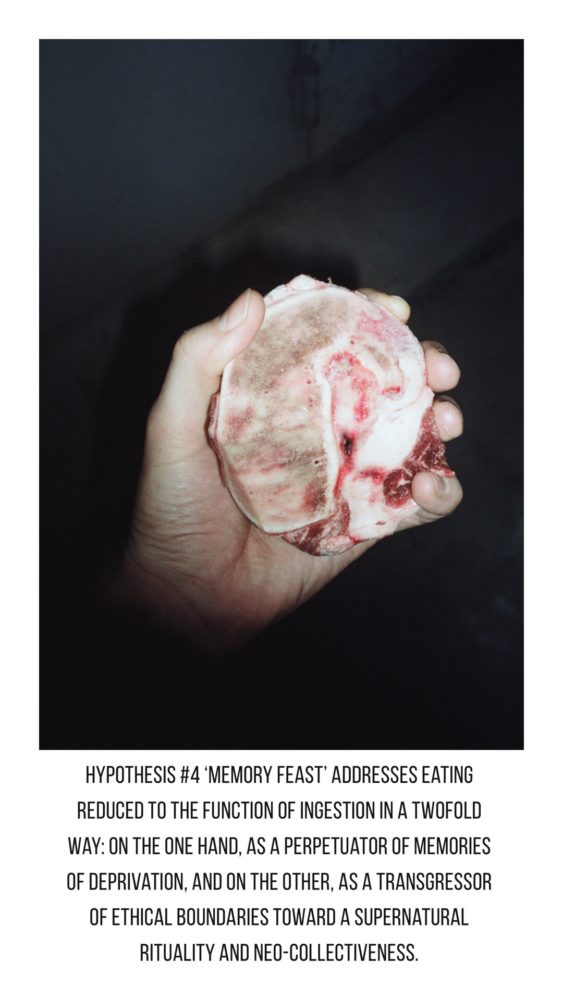

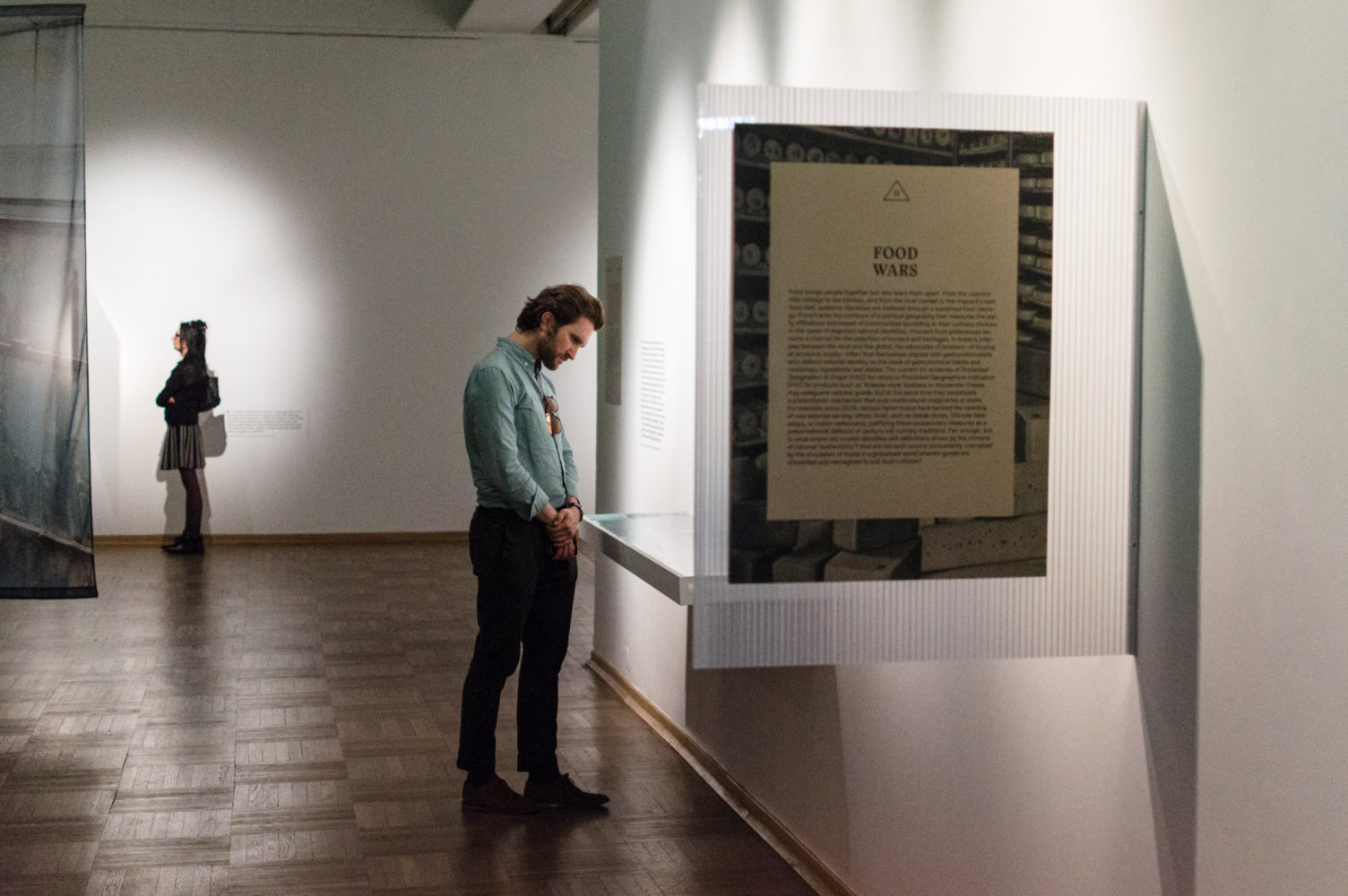

Among the four texts, ‘The Sacred and the Profane’ contemplates the ‘civilising’ role of gastronomic rituality in the naturalisation of our omnivore oriented food chain, and the subordination of the technologies of the self to collective belief systems and codes of ethical conduct. ‘Food Wars’ questions the extent to which the axioms of gastronationalism are today involuntarily corrupted by the circulation of foods in a globalised world wherein goods are reimagined to suit local cultures. ‘Docile Bodies’ plots the routes of displaced organic bodies (human, animal, and plant) on the world map, revealing a series of contradictory parallelisms. Lastly, ‘Memory Feast’ addresses eating reduced to the function of ingestion in a twofold way: on the one hand, as a perpetuator of memories of deprivation, and on the other, as a transgressor of ethical boundaries toward a supernatural rituality and neo-collectiveness.

Six artists have been invited to challenge and expand on these questions. Oscillating between fact/document and metaphor/symbol, past and present, and language and disarticulated speech, their respective projects establish a multilayered inner dialogue that unfolds against a set of dichotomies: nature vs. culture, individual vs. community, and spiritual vs. carnal/libidinal instincts.

Read more

Sinem Dişli presents two videos and an installation from her ongoing project Cereyan [Currents], which focuses on large-scale energy projects undertaken by industrial agriculture consortiums along the Euphrates (in historical Upper Mesopotamia), not far from the artist’s home town of Urfa, Turkey. Dişli looks deeper into the microcosm of communal culinary rituals passed on from generation to generation, such as seasonal bread making and animal slaughter. By tracing human–material interactions in contemporary Urfa back to their archaic origins, she provides a constructive reinterpretation of perennial rhythms, customs, and beliefs that continue to permeate her community up to the present day. By unearthing these practices as photogenic archaeological artefacts, she sheds light on the individual configurations inherent in them in spite of their apparent homogenisation and universality.

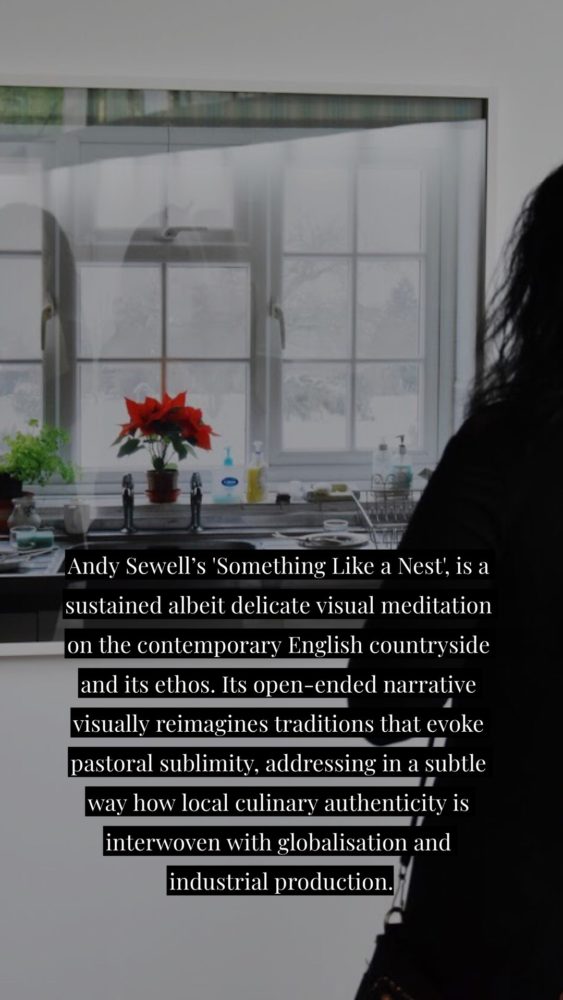

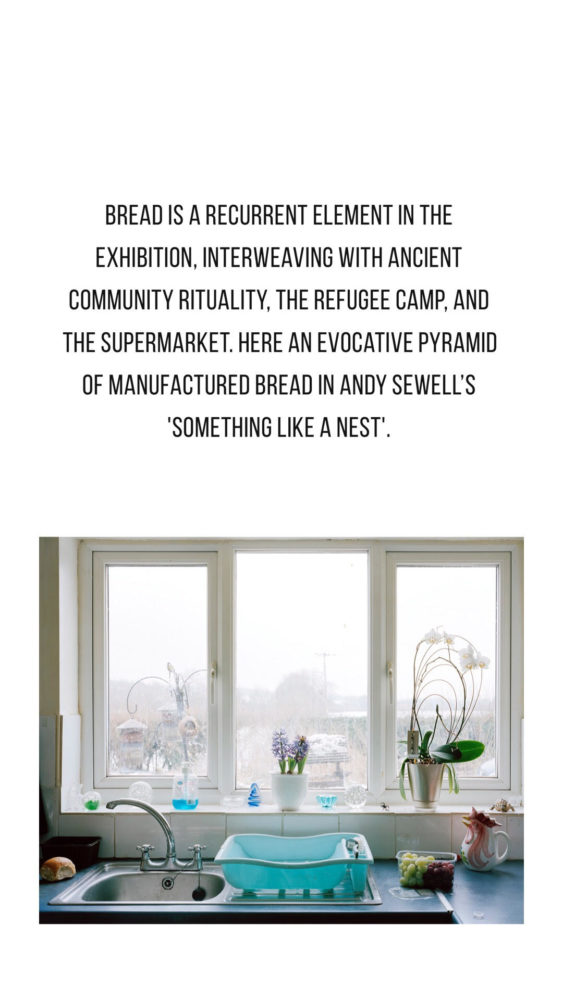

Andy Sewell’s series Something Like a Nest is a sustained albeit delicate visual meditation on the contemporary English countryside and its ethos. Its open-ended narrative visually reimagines traditions that evoke pastoral sublimity, addressing in a subtle way how local culinary authenticity is interwoven with globalisation and industrial production.

In One Third, Klaus Pichler explores food transportation and waste. An index of photographs of rotten aliments combined with reports on the story of their displacement, alongside an interactive world map, offers an insight into these two phenomena that are determined by a range of aspects: from geopolitical and financial factors, such as production, carbon footprints, and water requirements, to cultural histories and individual consumer behaviour. Taking into account that a significant percentage of food worldwide has to be imported owing to climatic reasons, Pichler’s work serves as an incisive examination of global inequality, while making the case that a consumer’s penchant for a particular food item is not simply a matter of lifestyle but rather a concrete political decision.

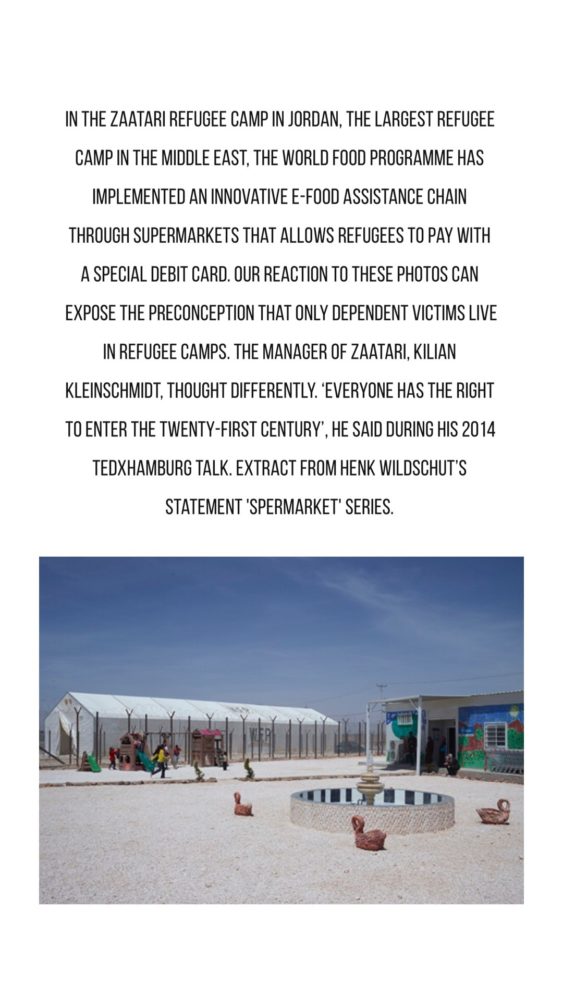

Henk Wildschut contributes three projects to the exhibition. Produced in the Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan, the second-largest in the world, Bread to Keep the Peace and Supermarket document the coexistence of two programs of food distribution implemented by the World Food Programme and its commercial partners: a traditional model of daily free bread supply via contracted bakers, and an innovative e-food assistance chain through supermarkets that allow refugees to pay with a special debit card. His third project, Food, commissioned by the Rijksmuseum and based on the artist’s in-depth research, employs a visual index and glossary of terms to demonstrate how food is industrially produced today, shedding light on various misunderstandings about the subject.

Ksenia Yurkova’s Spinebone Soup and Stuffed Rabbits multimedia project approaches the Siege of Leningrad as a case of the effectuation of a politics of death that casts its shadow across generations. At its core lies a reflection on the nature of food politics, hunger, and survival fare; the transition of biopolitics into necropolitics; the establishment of ethics as a product of a dominant ideology; and the role of trauma, memory, and speech in the shaping of consumer choice. The multiple languages of media with which she works (photography, video, installation) conflate different ideologies: here, a reference to the archival representation of plenitude neighbours the familiar tropes of consumerism, counteracting them with slogans of political counterpropaganda. The nourishing component of this general approach is reduced to a representation of a shell, a symbol, a signified without a signifier: to a speculative cookbook of words.

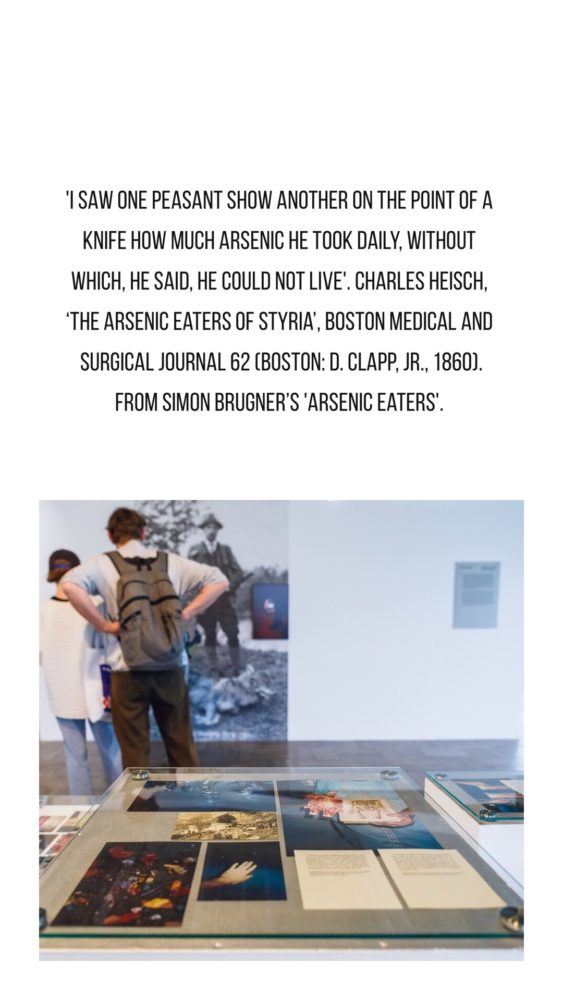

Finally, Simon Brugner, in The Arsenic Eaters, conducts a fascinating visual and cultural research on the taboo custom of eating arsenic, one of the most potent mineral poisons, common amongst peasants in nineteenth-century Styria, Austria. Departing from the widespread belief that the consumption of arsenic is beneficial to one’s health, Brugner’s survey expands on the pathos and metaphysics of eating the inedible. Reduced to the function of ingesting dangerous substances, eating is approached here as a subversive, self-empowering act through which individuals may attempt to transcend sustenance and fear, overcoming the limitations of the physical body and the societal and ideological structures that confine it.

Deliberately structured as an inconclusive and variegated tableau of circulating voices, artworks, and bodies, You Are What You Eat makes a pronounced statement of scepticism in regards to the current climate of political correctness and ‘fast-food ideologies’.[3] Its aspiration is to construct an inclusive space in which the pitfalls of identity and ideology are exposed, and where visitors are welcome regardless of their alimentary choices.

[1] ‘We can understand, too, that natural species are chosen not because they are “good to eat” but because they are “good to think.”’ Claude Lévi-Strauss, Totemism, trans. Rodney Needham (Boston: Beacon Press, 1971), 89.

[2] Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1998), 10.

[3] The term is used by political scientist Michael Freeden in: ‘Fast-Food Ideology’, Michael Freeden interviewed by Luka Lisjak Gabrijelčič, Razpotja 27 (July 2017), www.eurozine.com/fast-food-ideology [URL accessed March 9, 2019].

Curatorial approach