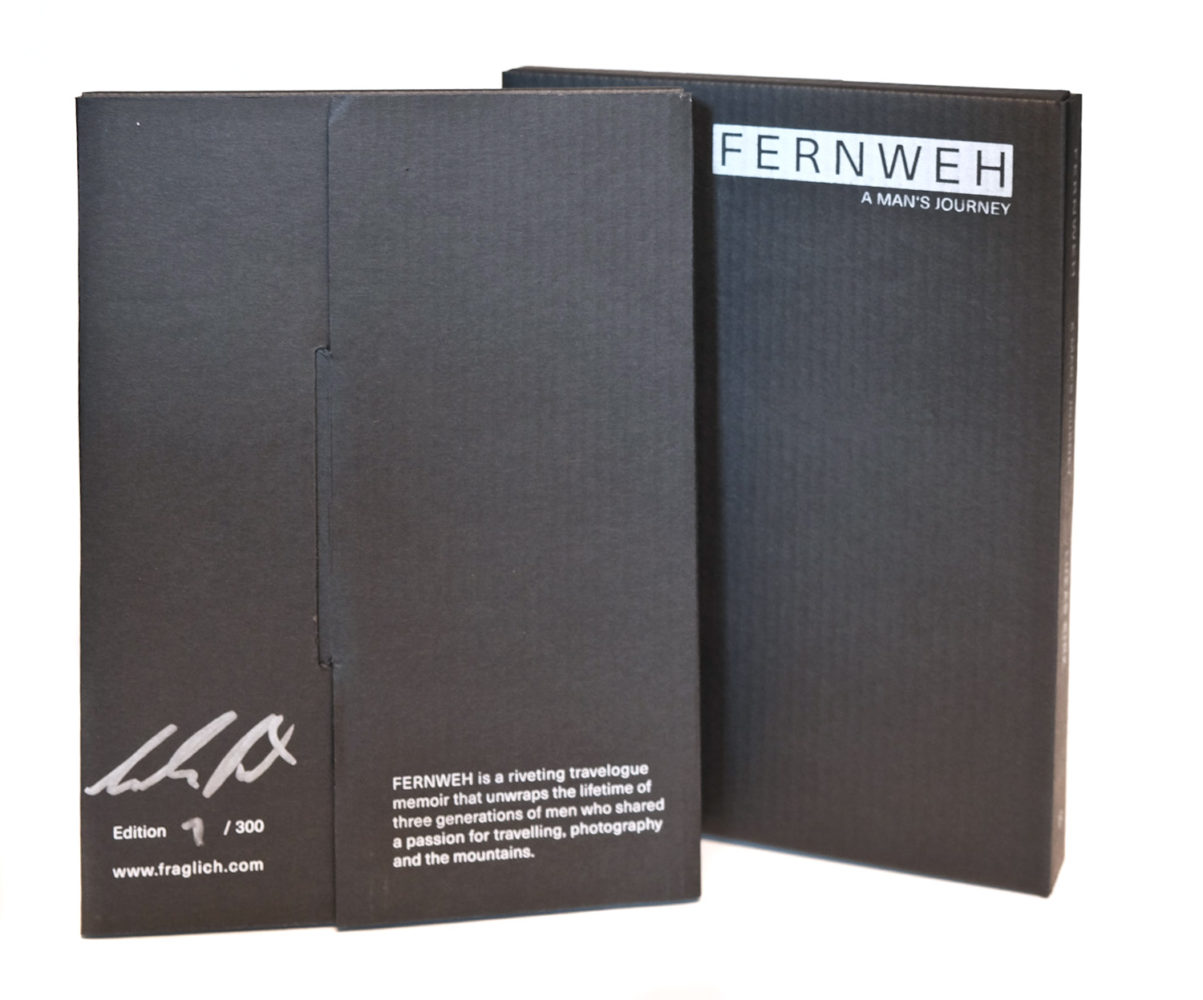

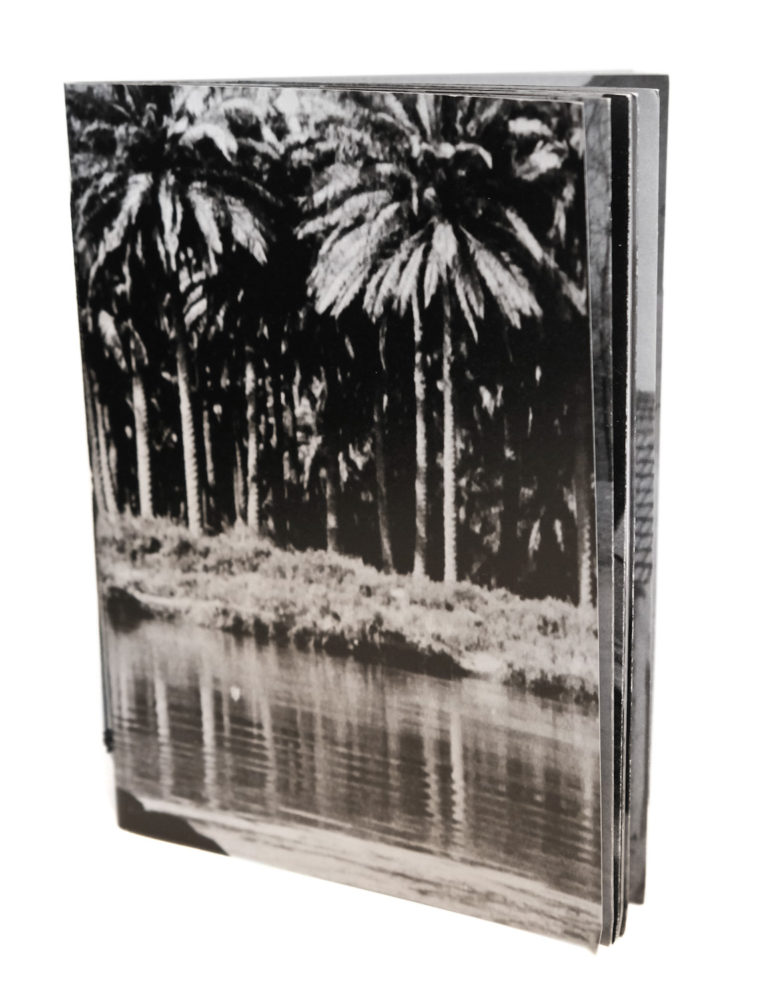

20x15cm

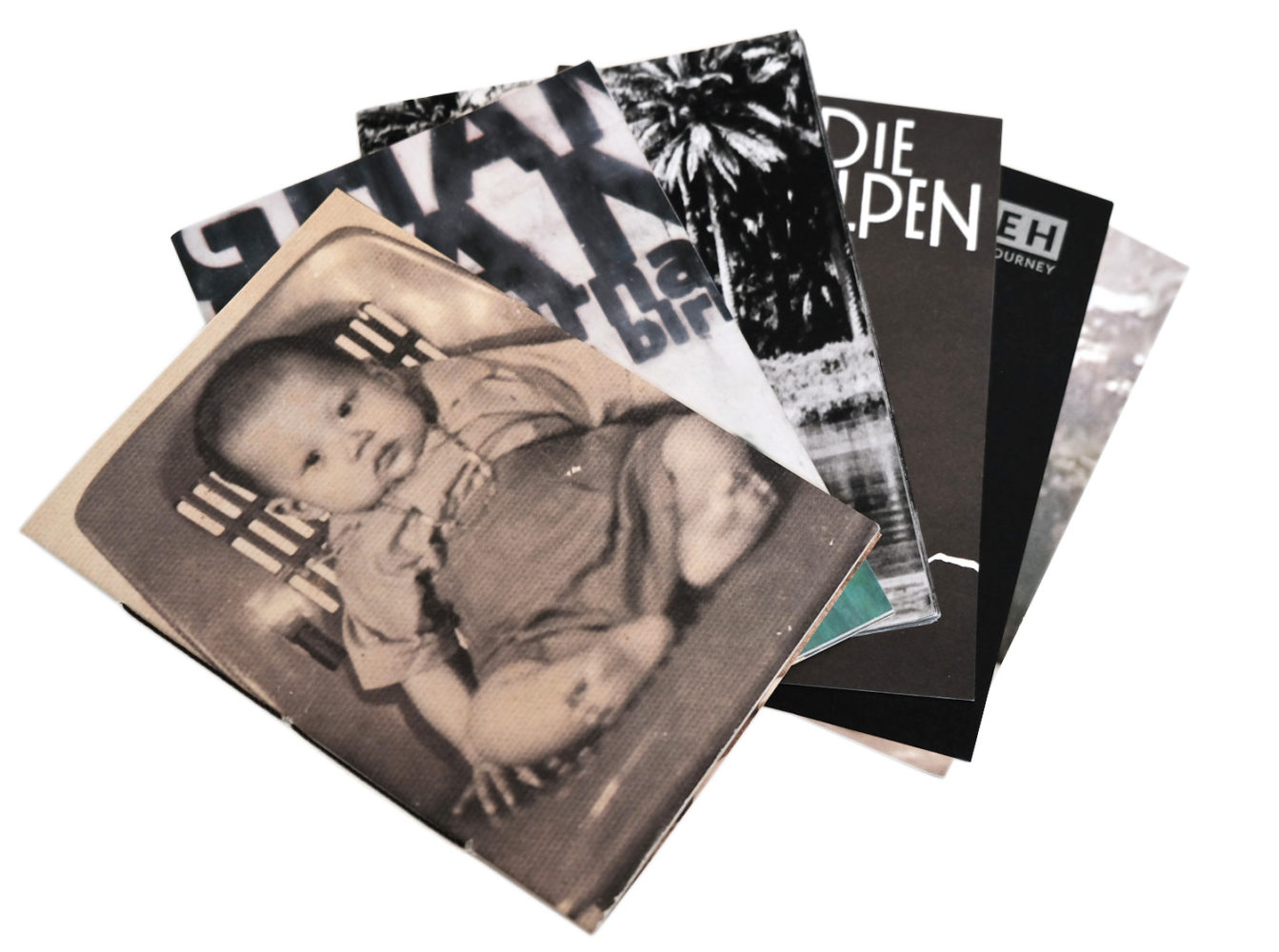

6 Brochures

The book was printed in five different countries and assembled into one box! From Delhi to Bregenz from Yangon to Istanbul.

With an introduction by Natasha Christia

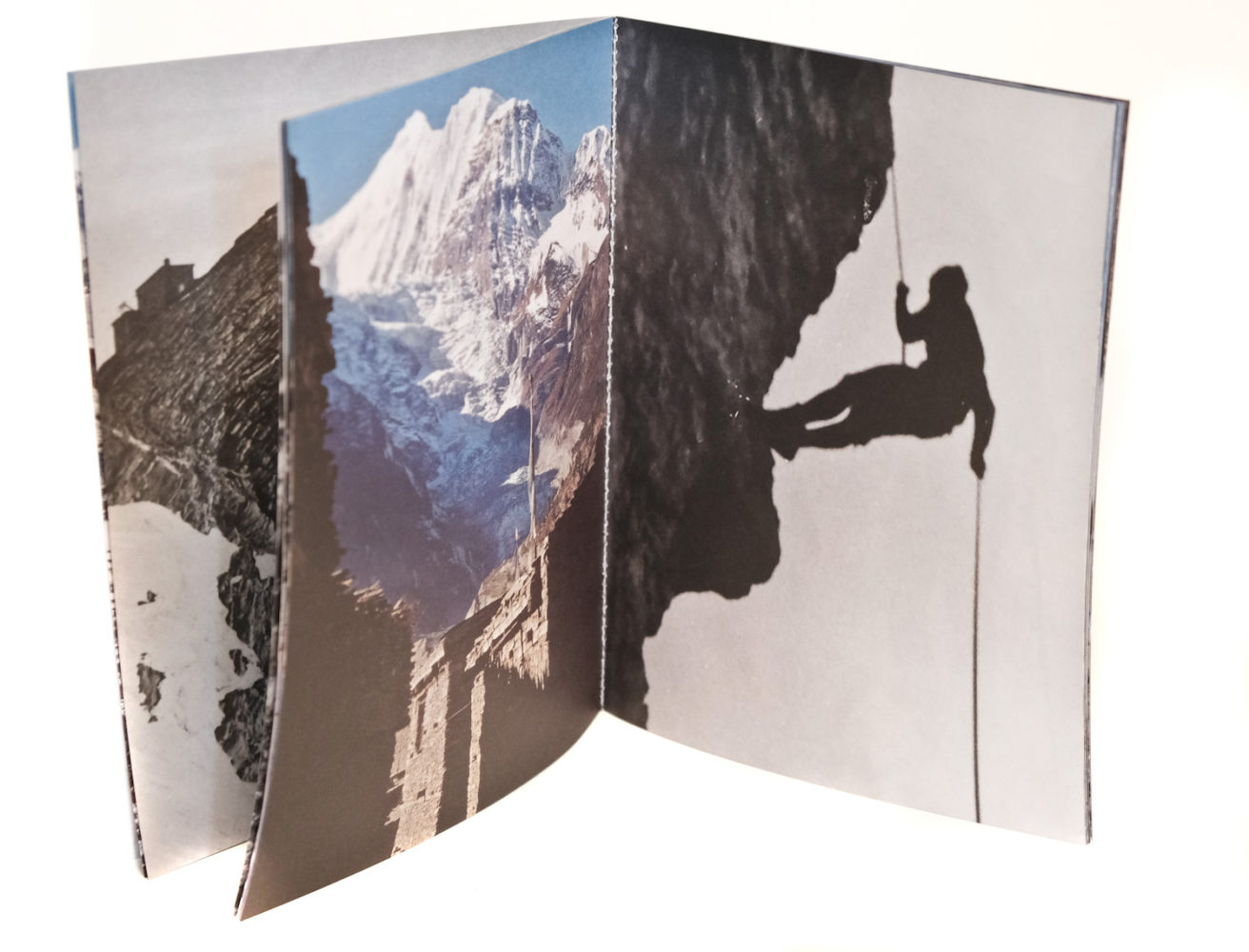

FERNWEH: A man’s Archive is a riveting travelogue memoir that unwraps the lifetime of three generations of men who shared a passion for travelling, photography and the mountains.

This publication was the outcome of the curatorial project that developed and conceived with Lukas Birk during 2017 as a mutating touring exhibition. After the conclusion of the project, we-coedited it and I contributed the final essay that wraps the project together.

Introduction

In FERNWEH: A Man’s Journey, storyteller, artist and collector Lukas Birk repurposes his extensive personal collection, comprised of visual memoirs of journeys that have taken place over seven decades in his homeland of Austria, the Balkans, the Middle East and South Asia. From vernacular to fine art photography and from the intimacy of the family album to ruthless public exposure, the product of this operation is a novel archival assemblage, both real and imaginary at heart.

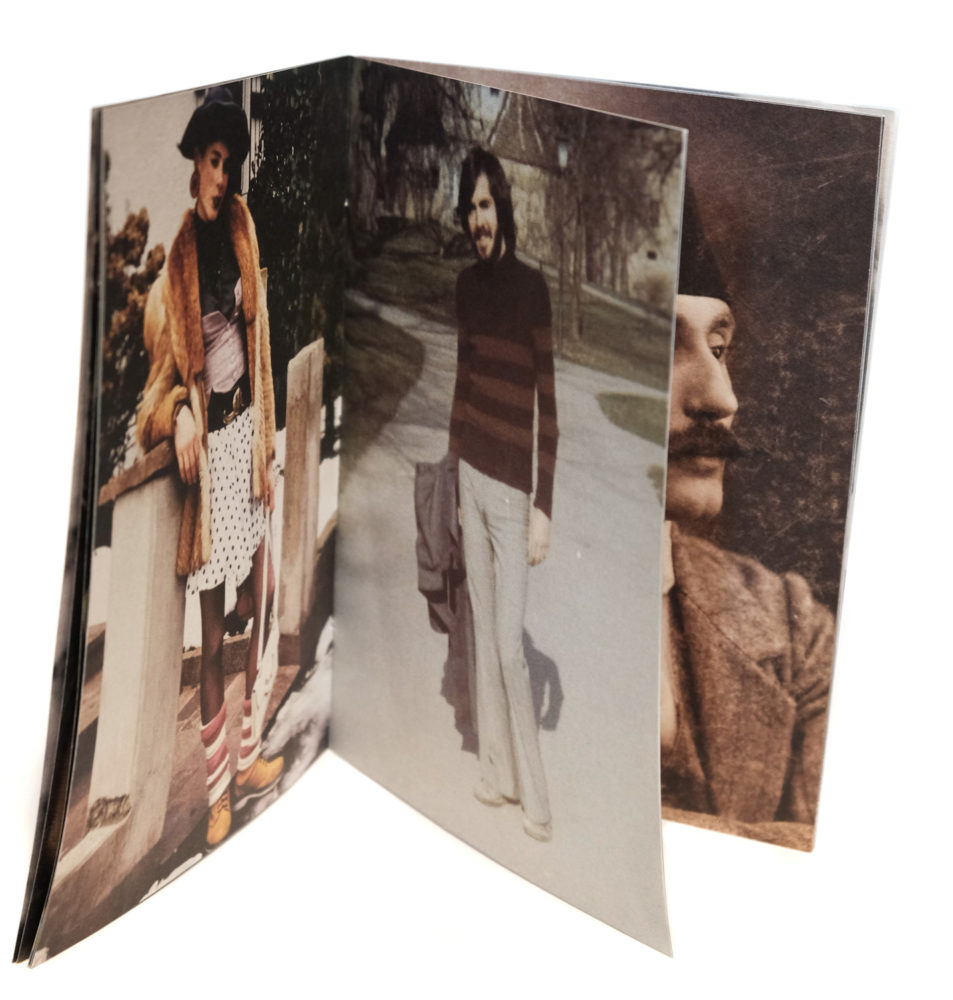

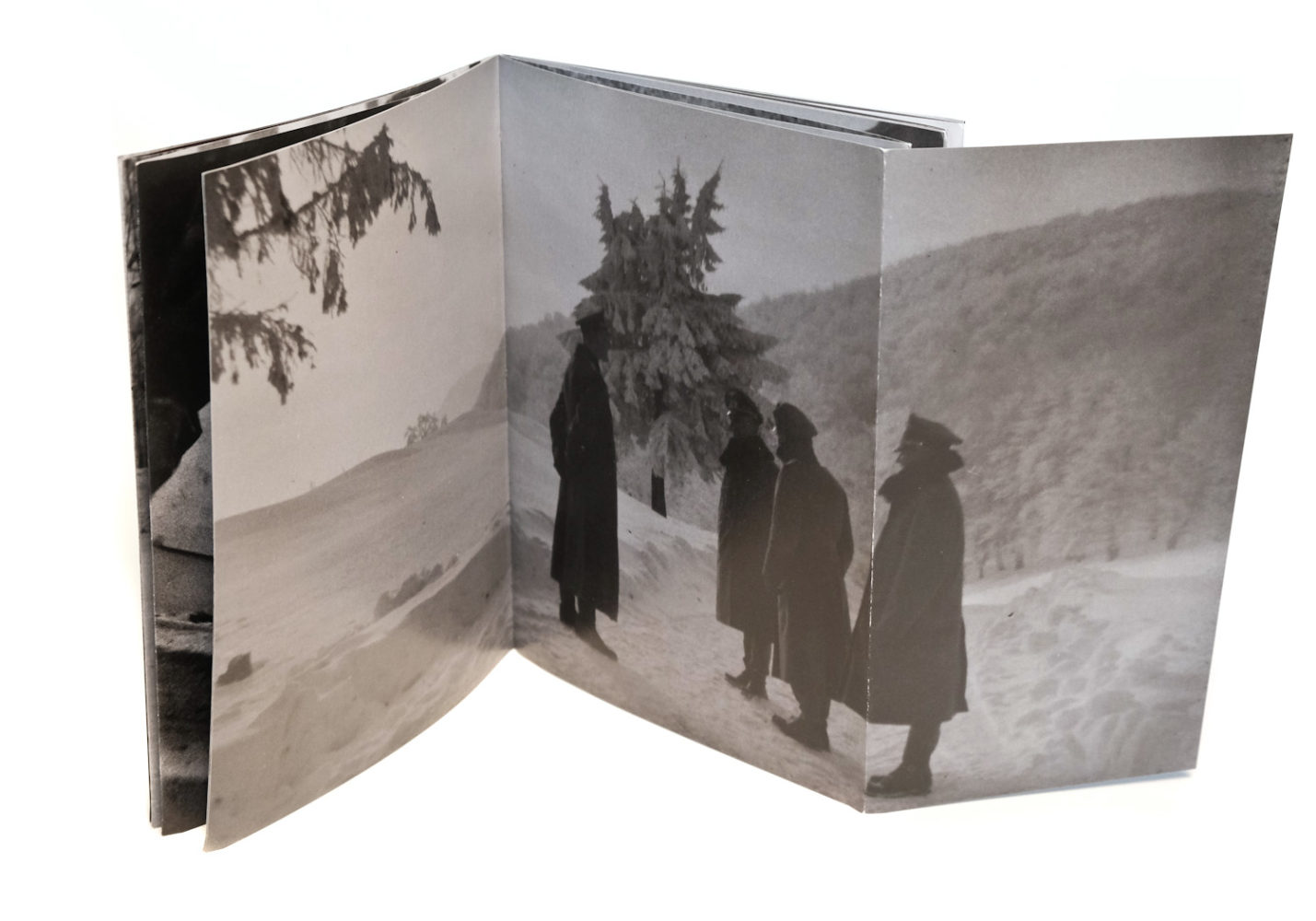

A remix of sorts, FERNWEH unwraps the lifetimes of three generations of men: Lukas’ grandfather Viktor Birk, who served as a soldier in the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany during World War II; his father Andreas Birk, a hippy traveller and adventurer of the 1970s and 80s; and finally, Lukas himself, a contemporary wanderer and artist. All of them shared a passion for travelling, the camera and the mountains.

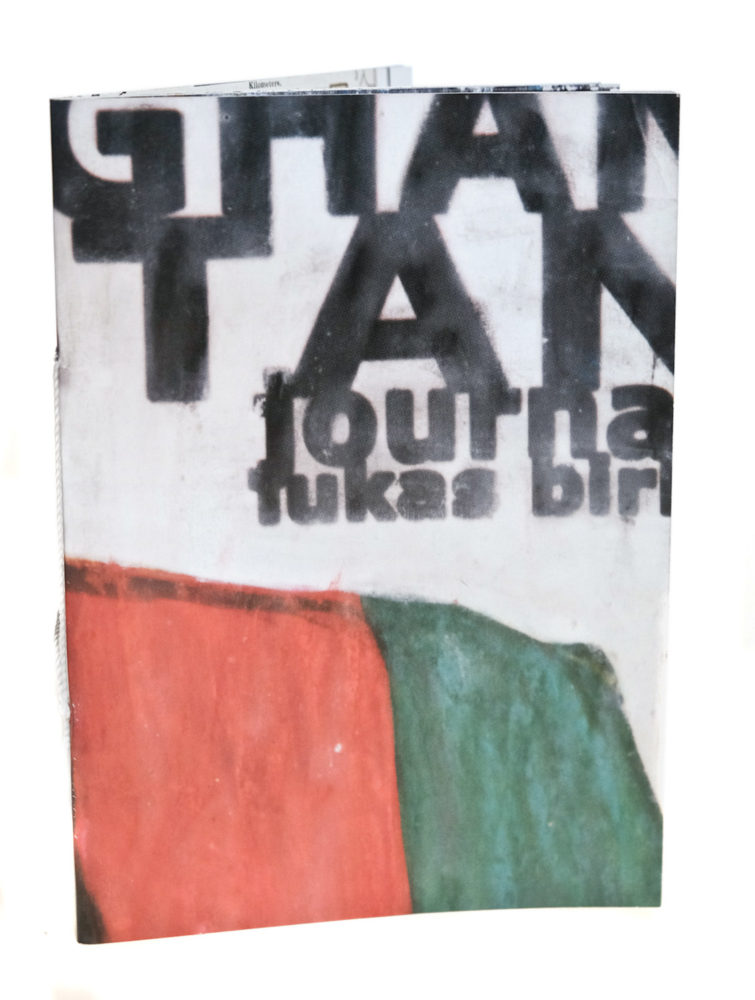

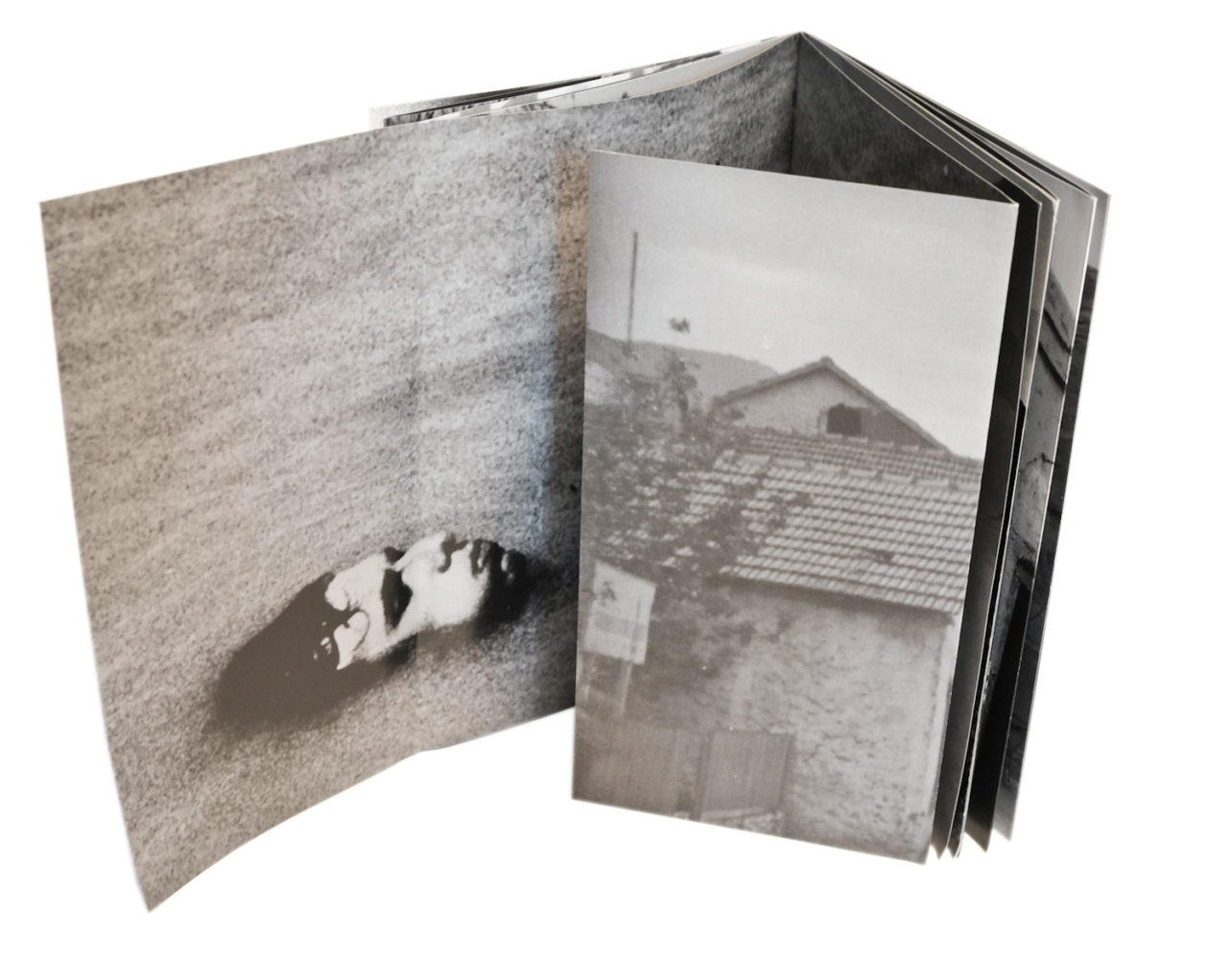

To bring this sophisticated albeit cryptic visual depository to life, Birk has referred both to his progenitors’ legacy and to his own history as an artist. Old travellers’ guides, maps and handcrafted Birk family photo albums of homeland mountain excursions and far-away road journeys coexist with materials from Lukas’ personal archive, such as prints, journals, travel memoirs, and portraits of anonymous men, all collected and/or produced between 1999 and 2017.

Some of Birk’s publications have provided the historiographical ground for the unfolding of the three timelines. 35 Bilder Krieg (2015) employs 35 negatives, found in an envelope, to reconstruct the route of soldier Viktor, Birk’s paternal grandfather, presumably in the Balkans, Paris and Greece during World War II, while Kafkanistan (2008) explores the world of present-day tourism while questioning the possibility of cultural identity assimilation in the conflict areas of Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan.

Perhaps the most significant material in the enriching and fictionalisation of the triple male plot of FERNWEH is a series of altered books: Atlas (a 1973 Austrian school atlas); 3 Bitef 212 (a 1969 Belgrade Theatre Festival catalogue); and Berg, by Luis Trenker (1932). The practice of embedding extra elements within their pages, such as photographs, album spreads, documents and annotations – all paramount in the shaping both of Lukas’ family history and his own identity as a travelling voyeur – has permeated the mash-up spirit of the whole project.

By displacing pictures and throwing them back into the arena of history, the narrative in FERNWEH expands further into a universal atlas of family stories and identity correspondences, reinforcing novel associations in the personal and collective memory. Amid its elaborate stratigraphy of collages, maps, recycled and new images, the three male protagonists and their storylines literally become one, merging with the lives of myriad others. A liquid amorphous identity arises and the timelines are carved into one non-linear and multi-voiced narrative that breathes within a dusty archival folder of scattered memories.

In this new storyline, the protagonist and subject – the Western and white privileged male traveller – is split. He is not situated in the central point of a central perspective but is rendered unrecognisable in order to partake with the ‘other(s)’ in a common tale. Through de-historicisation and the abolition of spatial and temporal references, a novel interpretation of personal and collective memory emerges, wittily seeking to revisit notions and clichés such as the male iconology of adventure and ascension to success, the trappings of exoticism, the ‘Other’ as a Western construct, colonial encounters, folklore and the status of the artist.

Here, Fernweh (a.k.a. the longing for far-off places) lies in an unconfessed dual relation with Heimweh, the craving for homeland. Bred by a romanticist escapism, these two German terms here articulate a quaintly nostalgic albeit ironic elegy to a chimeric ID-card identity that seems irremediably diluted and foregone. As a book object, FERNWEH performs this condition. The five booklets it contains are fragments of an incomplete photographic memory, misconstrued by nature. They also operate as interconnected vessels of a shared universal experience, inviting us to step back and forth in time and engage with content according to our own personal visual and emotional resonances. The only condition: not to lose sight of History’s fleetingness and finite triviality.

The book is available here