Centre Culturel Irlandais, Photo Saint Germain 2023

November 9-December 22, 2023

Curated by Natasha Christia

Supported by Arts Council Ireland, Photo Museum Ireland

LACUNA considers the physical and psychological impact of partition on the young people of the Irish borderlands. As Ireland marks the centenary of the 1921 Partition, Kate Nolan documents, through a series of photographs, audiovisual pieces, testimonies, archival footage and diverse recollected materials, the Irish frontier as a post-conflict space. Her counter-narrative, produced through dialogic conversations, informal pedagogy and participatory arts with youth groups challenges the fixity of the border and centuries of conflict. For those without that lived experience, understanding of the borderlands has often been seen through the lens of The Troubles, which lasted from 1968 until the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. Born after the Good Friday Agreement, the youth of the borderlands have never experienced a ‘hard’, militarised border. In the centenary of partition and even in the light of Brexit, the border is invisible to them. In their daily life, moving freely between the North and the South is a given. LACUNA exposes the frontier as a contentious line drawn on a map, in the name of political and colonial expediency. With little consideration of the natural or cultural particularities it encompasses, the Irish border, as any other, bisects the land and its people, enforcing rigid divisions. An in-between ‘third space’, it carries the latent imprint of a frustratingly fragile and cyclical past. It sustains echoes of trauma alongside hybrid identities, traces of colonial occupation, and the ambiguous trappings of language. The border is a cavity in understanding ¾a landless land of obscured details and unclear distinctions. Somewhere between night and dawn, it slips through the fingers like river water or smoke. What’s left for the photographer and her images is to become responsive to conversations and the myth of the landscape.

As our collaboration with Kate Nolan on the exhibit of her project progressed, a series of questions became more and more pertinent: how to echo, with honesty and authenticity, the collaborative nature of Lacuna? How to incorporate layers of historical information that are so essential for a fuller understanding of the theme, especially when it comes to an international audience?

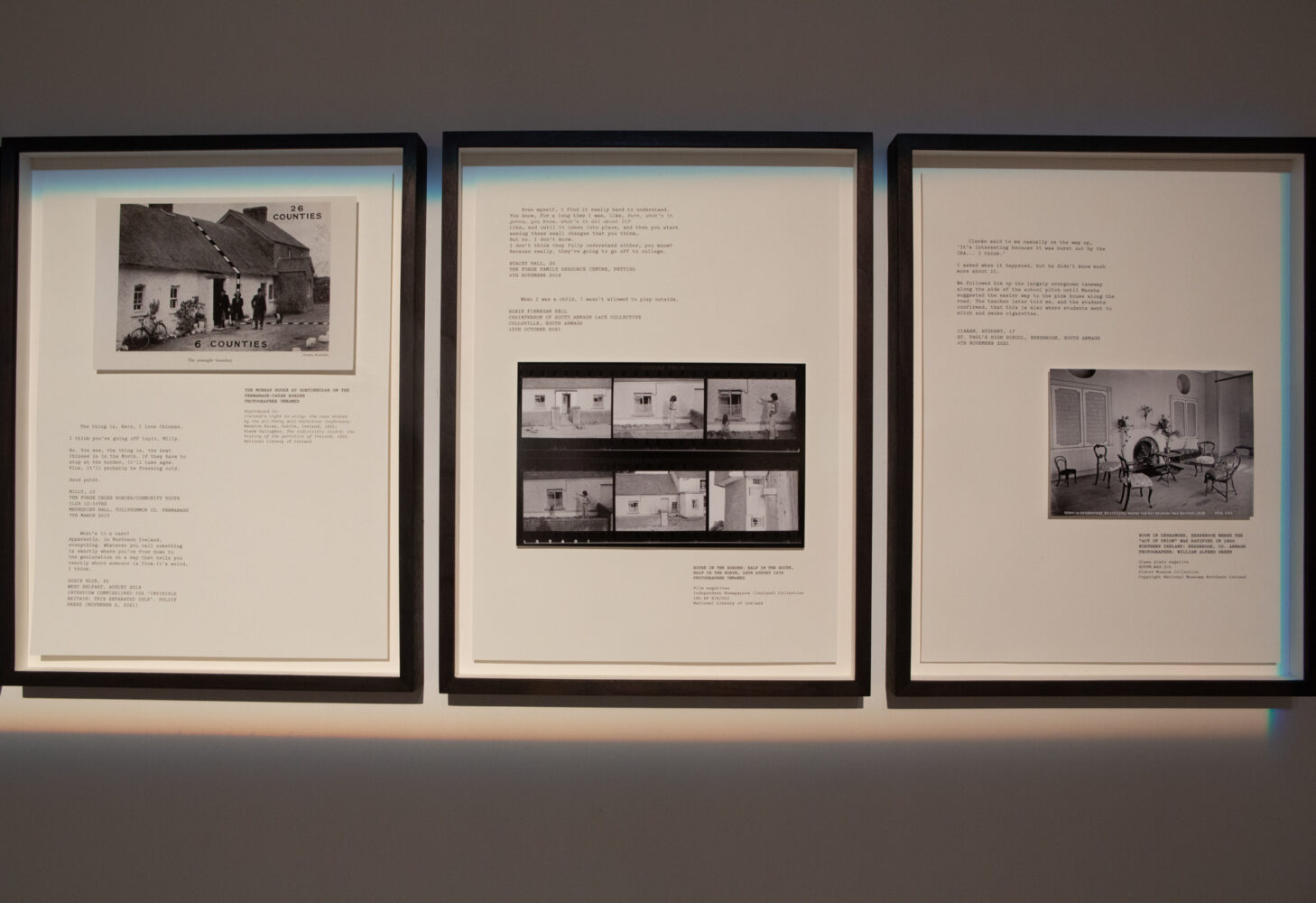

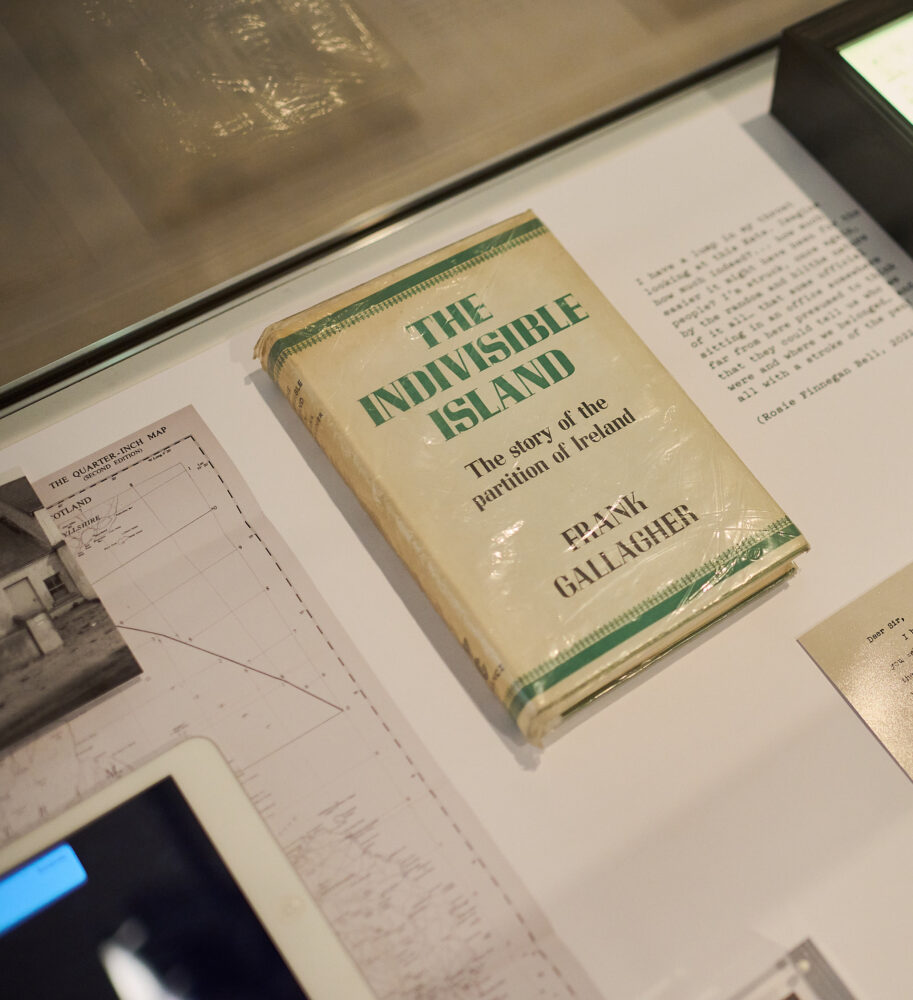

The outcome was an installation in which historical time is compressed within a single timeline horizon. There is not a clear distinction between past and present. Both enter in a dialogue here. A handful of reflections / visual reverberations take place in the physical space, and a new series of composite archival pieces propose new relations of timelines and voices. Within the same spatial frame, historical records or past photographic works on The Troubles, coexist with the oral testimonies of today’s youth. These new cohabitations reinforce a novel critical understanding of the existing ‘reservoir’ of representations of The Troubles that thrive alongside the official history and the less-heard oral stories. The artist acknowledges that she is part of a visual legacy of borderland photographers and storytellers. At the same time, she allows, through visuals and words, space to these, usually overlooked, middle spaces in historical narrative -that is to say, the daily lives, practices and rituals of people whose destinies are irremediably determined by the politics of the border.’

The relevance of Nolan’s approach lies in her quest to document the human experience of a post-conflict space, through the perspective of young people who are literally obliviated by the politics of boundaries. Next to the iconic visual legacy of The Troubles and the grand national narratives, she employs a series of photographs, audiovisual pieces, testimonies, archival footage and contemporary visual materials, to draw attention to familiar stories and voices that unveil the daily affective bonds unfolding in the border-lands. There was a turning point in her six-year engagement with the subject: acknowledging with honesty that in order to create new representations of the territory, it was necessary to move past the familiar practice of observation and visual documentation, or even the mere transcription of an interview, to a position of critical listening – to what sociologist Les Black calls ‘progressive listening’. In the installation, we attempted to incorporate the experience of listening through two sources of sound – two voices that accidentally conflate in some areas of the space, in their attempt to find their way to our ears.