A Series of Formulations on the Musealisation of Photography. Commissioned essay for Thing, Aura, Metadata: A Poem on Making. Over Magazine issue 1 2020 / Originally published in the catalogue of the homonymous exhibition curated by Ayn Seda Yildin for Parallel-European Photo Based Platform and Photoireland Festival 2019, pp. 30-33.

# Profaned Monumentality

In his book On the New, Boris Groys argues that an ‘artwork looks really new and alive only if it resembles, in a certain sense, every other ordinary, profane thing, or every other ordinary product of popular culture’.[1] Likewise, he describes the museum as a confined controllable space in which it is possible to stage, perform, and envision the world hors les murs, as ‘splendid, infinite, ecstatic’. The museum dictates this ‘out-of-bounds infinity’; it delineates this exceptionality wherein things are the same but at the same time different, allowing us to imagine its outside as ‘infinite’.[2]

Today, the condition of polarity is globally manifested and accentuated in both the physical and virtual/cybernetic realms. For many, virtuality has taken over matter. But life holds in reserve the sorts of unexpected twists that rip manifestos to one million pieces, and the tank, as Hito Steyerl has remarked, is driven off its public pedestal to be redeployed to the battle.[3] What is the last remaining affirmation and condition for Groys—the walls of the museum—collapse. The rupture is violent; it is not just about a concrete wall, but about the art collection existentially reforged into an arsenal of war. Battle and destruction invade the museum. Performed repeatedly, they impound its artworks and canonise the right to destroy.

Read more

This idea of displaced and profaned monumentality tantalises me. But rather than the tank, what haunts me is the image of its decrepit and empty pedestal. It is not the first time we witness it. Thirty years ago, with the fall of the Berlin Wall, many tanks rumbled back to war. Back then, everyone, and not just Francis Fukuyama,[4] was predicting the end of history.

Three decades later, history hasn’t, in fact, gone anywhere and rather than cease or vanish, I would describe its current condition as being one of fatigue. If, ‘in the mid-nineteenth century, museums and memorials were created to accommodate and institutionalise the yearning for the past’,[5] now, in an era of cybernetic flow, what they shelter is the exhaustion from pretending that there are historical events to pay tribute to and a past to long for. The displacement of the tank from its pedestal helps unmask the violence that has lain there dormant but veracious. As Ariella Azoulay puts it, statues do not just die, they are murdered.[6] With the exceptionality they bestow through their taxonomies (collections and exhibitions), museums exercise sovereign power over the bodies of their artworks. From a radical angle, their ‘state of exception’ could be seen as similar to that of the camp. Walter Benjamin was more than right in his brilliant insight: ‘There is no document of civilisation, which is not at the same time a document of barbarism’.

# Fatigue

The association of photography with fatigue and a profaned, deposed monumentality is a hypothesis that intrigues me when it comes to developing a new agenda for the medium’s future musealisation. To my eyes, photography’s fatigue emanates not from what images can or cannot tell us, but from the medium’s intrinsic self-referentiality which, at times, leads it toward an excessive self-indulgence. I am tired of the anachronistic deployment of the term ‘photography’, and of the persistent quest for a ‘museum of photography’ as an avenue toward legitimisation. I am tired of outdated redundant theory; of the medium’s naive visual purism, which alleges that an image is equivalent to one thousand words; and of its gushing over transgression while its narrative modes and exchange values still operate within a more or less conventional frame. Lastly, I am weary of our lack of humbleness when it comes to acknowledging photography’s limitations. What is truly unlimited is the ‘photographic’, and it can be found everywhere, not just on photography’s patch.

As far as profaned monumentality is concerned, photography is a promising field. For many years, its status within the museum was questionable—the veneration of reproducibility, the document, and the archive was still due to arrive. And yet, within the industrial era’s epic nostalgia of loss, photography and museums go hand in hand. Both have solidified as institutions of social, cultural, and emotional reform. Both have been wielded as ‘imperial devices of control’, ‘non-accountability’, and ‘expropriation’.[7] In both cases, walls are currently in a state of collapse. Their public and private sovereignty is subjected to a temporal and spatial fluidity regulated by digital technology. In point of fact, photography’s walls were never meant to be firm. Photography, writes Andrew Dewdney, has never been ‘a single technical entity nor a unified philosophic vision’. It is ‘a hybrid of related technical apparatuses, social values, cultural codes, media forms and contexts of reception’,[8] and as much so as the museum. For its part, the physical museum, as a complex performing cell of material and visual culture, has no less a role to play in the realm of visuality and its discourses than photography.

I envision photography’s institutional future, and my sight becomes flooded with the manifestations of a lens- and algorithm-based culture. From traditional cameras to camera phones, from fine-art prints to digital online curating, and from the still to the moving image and their intermediate constellations, I see photographic images, the same as any other artwork, as precious collectible entities and, simultaneously, as immaterial operational metadata, with their autonomous aura fluctuating between uniqueness and banality. I see them as mutable associative laps that circulate from one narrative to the next; as devices of power; and as receptors and transmitters of gazes. I see images of artworks, and artworks themselves, as mental images in the viewer’s mind. I see a museum, with or without walls, as a physical or virtual condition that crystallises as an image of itself.

Amidst an ecosystem of ‘accelerated capitalism and its computational logic’,[9] museums are here to rethink the world by, in part, ‘un-thinking’ photography as it has been heretofore formulated. To un-think photography means to reveal it as a ‘paradoxical sum of its technological apparatuses and cultural organisation, rather than simply the ascendency of representation’.[10] It also means to determinedly defy its predominant, simplistic implementation as an axiom by anachronistic modes of visual storytelling and curation.

I dream of a ‘museal pedagogy of emancipation’[11] that confronts us with the ways in which both physical and virtual images condition our gaze and our terms of engagement with representations, wilfully challenging the chasm between prevailing cultural codes of visuality, computational codes, and hegemonic taxonomies. I dream of a museum that, overcoming the medium’s claustrophobia, rethinks photography’s boundaries with other cultural agents, society, and technology—even at the risk of allowing in discordant noise—so that we are no longer asked to curate photography collections or photography exhibitions, but, simply, collections/exhibitions of material and mental dialogues. In this space of re-readings, or even battles, photography should be regarded as what it primarily is: a relational apparatus, in a ceaseless process of re-contextualisation and de-contextualisation, that has the ability to dismantle the ideological and monumental structures of the past, the present, and the future.

# Profane Collisions and Revolutionary Illuminations

To paraphrase Boris Groys’ words at the beginning of this essay, it is precisely because of photography’s absolute resemblance to ‘every other ordinary, profane thing’ to be found beyond the walls of the museum that the medium can project a vital freshness. Photography is a fascinating but, a priori, exhausted heterotopia. Its critical and empirical capabilities lie outside the frame, in the assumption of identity as a relation. There are still many of us who search for answers upon the opaque surface of the image, but the latter catapults them out of its domain toward an archipelago of misrecognition. For every photograph implies an eminently self-reflective, radical unmasking of hegemonic dichotomies that potentially carries within it the possibility of innovation. Be aware, nevertheless, this revolt may also involve profanation, conflict, and destruction. And battle. I envision the museum hovering spread-winged above this scenery of battle, like Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, described by Benjamin as the ‘angel of history’ in one of his most brilliant essays. Behind him, a ‘catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage’. In front of him, ‘the future’.[12] I do not see the pile of debris from here, but I do see an empty, decrepit pedestal bearing the ghostly imprint of the hauled-away monument. A photographic image, scratched, creased, and begrimed, lies upon it, to be shared, co-created, and transmitted with and by all of us. The photograph as a means to enter a new horizon of world dialectics based on an equality of access, knowledge, and experience. A record sufficient for the apprehension

[1] Boris Groys, On the New, trans. G. M. Goshgarian (London: Verso, 2014), 18.

[2] Ibid., 19.

[3] Hito Steyerl, ‘A Tank on a Pedestal: Museums in an Age of Planetary Civil War’, e-flux 70, (February 2016), e-flux.com/journal/70/60543/a-tank-on-a-pedestal-museums-in-an-age-of-planetary-civil-war [all URLs accessed 10 May, 2019].

[4] Cf. Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press, 1992).

[5] Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001), 15.

[6] Ariella Azoulay, ‘Looting, Destruction, Photography and Museums: The Imperial Origins of Democracy’, lecture, Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona, 28 March, 2019.

[7] Azoulay, 2019.

[8] Andrew Dewdney, ‘Co-creating in the Networks: A Reply to “What is 21st Century Photography?”’, The Photographers Blog (January 4, 2016), thephotographersgalleryblog.org.uk/2016/01/04/co-creating-in-the-networks-a-reply-to-what-is-21st-century-photography.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Manuel Borja-Villel, ‘Debemos desarrollar en el museo una pedagogía de la emancipación’ [We Must Develop in the Museum a Pedagogy of Emancipation], El País (November 19, 2005), elpais.com/diario/2005/11/19/babelia/1132358767_850215.html.

[12] Walter Benjamin, ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 257–258.

Yusuf Sevinçli: Oculus. 1000 Words. 10 Years, 2019

In “The Rest is Silent,” French filmmaker Chris Marker takes us back to the ‘cinema of origins’[1]: shadowy, imprecise, monochromatic. Contrary to what one would be inclined to believe, black and white was not a mere by-product of the technical limitations of the ‘so-called silent era.’[2] It was a choice. ‘A refusal of nature’s original seduction’,[3] it fostered an alternative mode of visualising reality, and a turning point: from 1900 onwards, Marker playfully attests, ‘people started to dream in black and white.’[4] The collective unconscious of the nascent film and photography industries propagated a colourless view of the world while it inaugurated ‘an era of imperfect memory’.[5] If photography was the first of the arts to freeze time, it would also perpetuate its presumed weakness: fugacity. Its stasis flagrantly suggested that there would always be a before and an after in a world of immanence and constant flow.

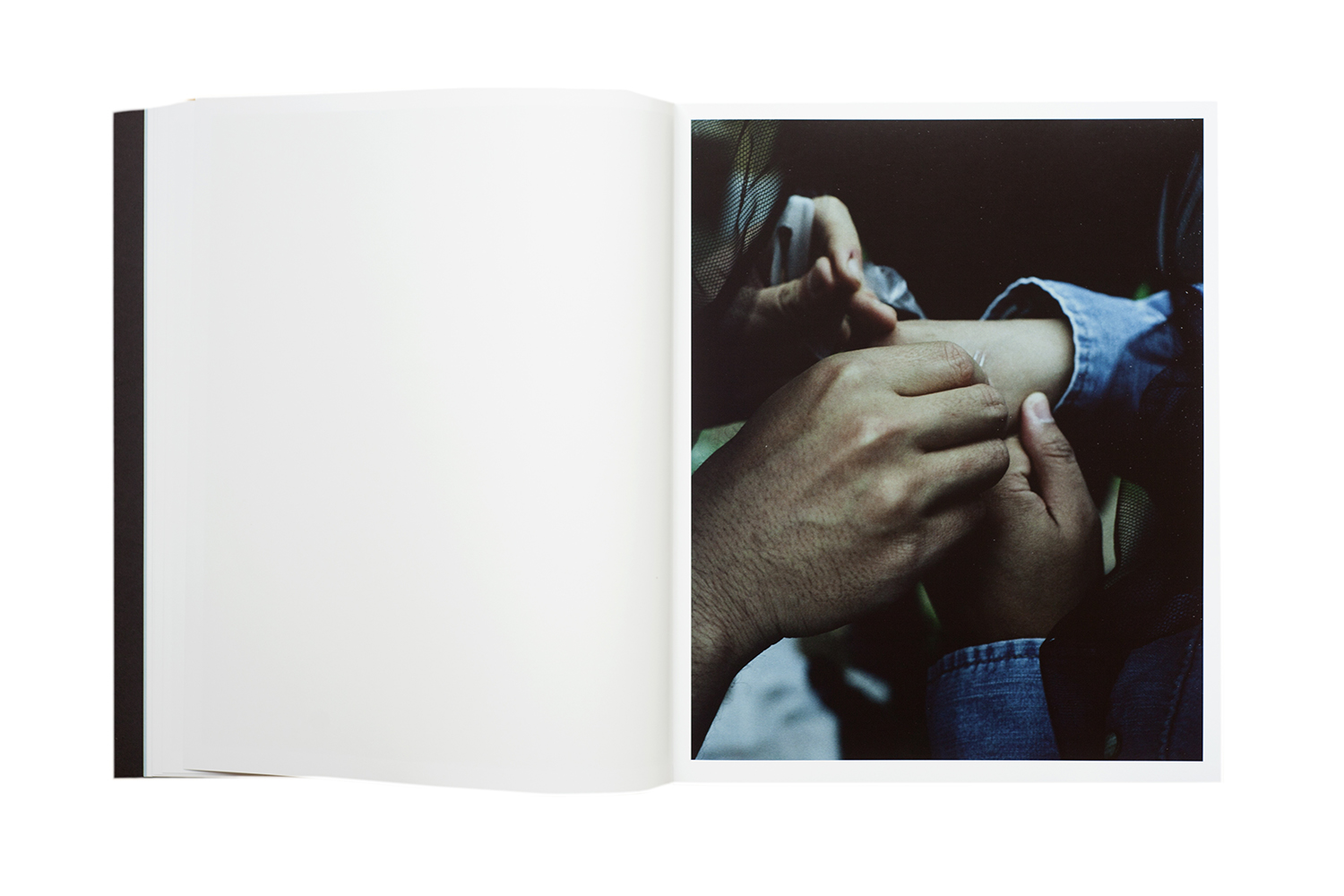

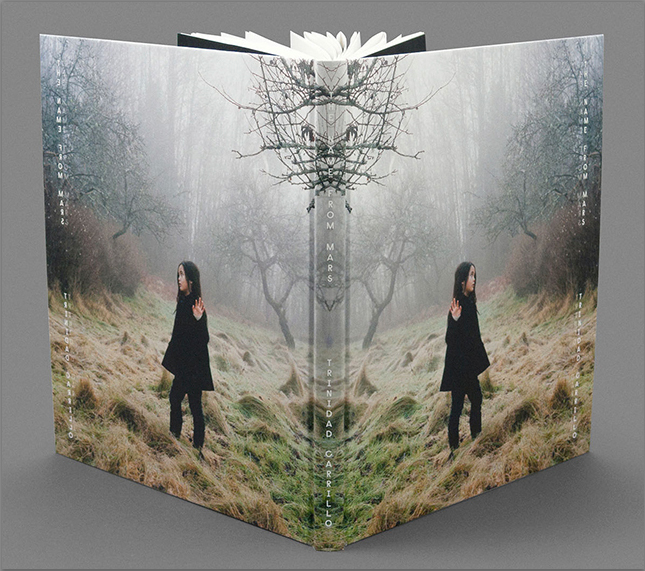

I cannot refrain from referring back to Marker when contemplating Oculus. Its creator, Turkish photographer Yusuf Sevinçli, describes it as a time- and site-specific assemblage of photographs from various projects[6] that has culminated in an exhibition hosted by Galerist in Istanbul[7] and in a concertina book object edited by Valentina Abenavoli. Oculus defies the contemporary quest for storytelling. A cryptic palimpsest of scattered visions, it incites an open-ended contemplation free of elaborate conceptualisations. Its images entice me to transcend the universe of words, to daringly acknowledge that here, in the mass of volumes, shapes and bodies Sevinçli explores, there is nothing to be said, nothing to be written.

Read more

In his essay, Marker argues that ‘[t]here was never anything like silent cinema.’[8] He vividly recalls the figures of the narrator and the piano player in the movie theatres of the times. Both employed their ‘imaginary forces’ to ‘fix’ the audience’s emotional responses to the screened pictures.[9] What has presumably remained mute is photography. And yet, Sevinçli’s pictures are inhabited by inner whispers. Their voluptuous materiality imposes itself; and this has a reverberating effect, rendering each image a graphic equivalent of a natural and psychological duration that condenses its creator’s internal chords.

These are not pleasing photographs. Aestheticising them would violate their essence. Alimented by the modes of the ‘stream-of-consciousness‘ tradition,[10] their strong formalism proves misleading when it comes to their reading. They are sensuous, emotive and fragile, but at the same time rough, untamed and feverish. As Sevinçli declares, “What I photograph belongs to me.”[11] His oeuvre carries the hallmarks of this arbitrary imposition of rules by a photographer who regards himself first and foremost as an image-maker.[12] Captured with various analogue cameras during his everyday life, and manipulated in the solitude of the darkroom, Sevinçli’s images are the culmination of an instinctive and intensely subjective processing of reality. They are material manifestations of an avid recollection of disparate moments at the threshold of personal and collective history. Transitions in them are abrupt and crude: from inner to outer space, from darkness to light, from the past to the present, and vice versa. They are indecisive and fluid, the way dreams are but without being dream-like. It is actually dreams and reveries that have become photographic. Not just in terms of their colour(lessness) but as successions of non-crystallised images destined to contain the vanishing point of the past. In a world where people seem to have lost all sense of reality, history has become synonymous with dream and subjectivity has won over. This condition enables Sevinçli to transcend the spheres of personal and collective experience, without the need to be explicitly political. His editing for Oculus literally somatises the current instability in his home country, Turkey. It transmits restlessness as a psychological symptom of a polarised world. His leaning bodies and bending trees denote a prolonged state of transition that is deemed to last forever.

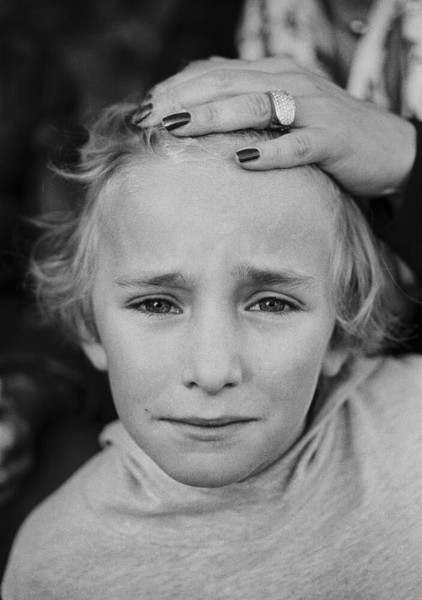

Looking at Sevinçli’s pictures, the late experimental filmmaker Peter Hutton comes to my mind. Hutton would spend hours and hours recording static shots of subtle shifts for his cinematic sketchbooks of cities and landscapes. His silent, 16mm movies are articulated as loose, anti-associative slideshows in motion. Sevinçli’s images have a similar quality. They condense the passage of seasons, and the irremediable decay of natural forms, bodies and souls. They are reminders of the fact that through photography we can see much more than we can understand. They resurrect that state of perception ‘anterior to understanding, anterior to conscience’,[13] and take us back to a grainy shadow land where flesh reigns. Bodies here exist as nothing but dismembered entities, as cries reaching out for someone, something. Even children’s faces emerge as the imprints of an unstated desire for raw human experience. Perhaps these pictures are a declaration of their proper materiality. In attempting to recover this primordial moment, Sevinçli acknowledges both the reach and the limit of the photographic act, that conflicting state of trying to grasp but being unable to.

Sevinçli seeks to reduce his visual work to a minimum: to produce exhibitions and books with fewer than ten pictures; to find the right image – an image that means the whole to him.[14] His Istanbul installation included, next to twenty-five conventionally exhibited photographs, a chamber with hundreds of test prints hanging from the wall. Entering this cavern-like space, the viewer is taken on a journey into the mind of the photographer. The search for the right image goes on, incessant and frenetic. It manifests itself in the antagonistic interplay of light and shadow in every one of his images.

In an otherworldly picture of a gleaming window,[15] this latent palpitation erupts into an opaque mass of white light – a portal that subsumes all past, present and future emotion. Here the search for the absolute image ends for me.

Oculus traces the passage from our uncertain world to a shadowy period before photography’s precise flashes and structured mythology. For the last time, I retrieve Marker’s thoughts as I bear witness to Sevinçli’s ‘images of gods and goddesses, united, disorderly, full of gaps and black holes,’[16] emanating out of a cosmogony of chaos. Darkness becomes an image in itself, and light a step towards the epic recovery of a crystal clear memory that defies intelligibility in favour of the fantastic realm of the absolute image.

[1] Chris Marker, “The Rest Is Silent,” in La petite illustration cinématographique: Chris Marker, Silent Movie (Columbus: Wexner Centre for the Arts, The Ohio State University, 1995), 17.

[2] Chris Marker, “The Rest Is Silent,” 17.

[3] Ibid. 18.

[4] Ibid, 17.

[5] “Chris Marker: Notes from the Era of Imperfect Memory”, https://chrismarker.org/

[6] Skype interview with the artist. 14/06/18. Is it necessary to add this???

[7] http://www.galerist.com.tr/en/artist/yusuf-sevincli/biography/ (to consult with Tim)

[8] Chris Marker, “The Rest Is Silent,” 15.

[9]Chris Marker, “The Rest Is Silent,” 17.

[10] Gerry Badger, “The Indecisive Moment: Frank, Klein and ‘Stream-of-Consciousness’ Photography,” in Martin Parr and Gerry Badger, The Photobook: A History, Volume I (London: Phaidon, 2004).

[11] Interview with the artist.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Chris Marker, “The Rest Is Silent,” 17.

[14] Interview with the artist.

[15] No endnote necessary here: Reference to the picture shown in the magazine? To include it.

[16] Chris Marker, “The Rest Is Silent,” 17.

Copyright: Natasha Christia/1000 Words 2019.

Tom Griggs and Paul Kwiatwowski. Ghost Guessed. 1000 Words 28. Summer issue 2018

‘Imagine you are falling. But there is no ground. (…) Paradoxically, while you are falling, you will probably feel as if you are floating –or not even moving at all. (…) As you are falling, your sense of orientation may start to play additional tricks on you. The horizon quivers in a maze of collapsing lines and you may lose any sense of above and below, of before and after, of yourself and your boundaries. Pilots have even reported that free fall can trigger a feeling of confusion between the self and the aircraft.’

Hito Steyerl. In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective. e-flux journal #24, 2011.

Ghost Guessed by Tom Griggs and Paul Kwiatwowski is a brilliant meditation on disorientation amidst a groundless world of increasing digitisation, expanded horizons and prolonged absences. In their book, the voice of a narrator is deployed to bring together two stories centred on the theme of loss: firstly, the tragic accident of a young pilot, Grigg’s cousin Andrew Lindberg, who crashed while on his way to a hunting trip in northern Minnesota in 2009; alongside the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 in 2014, undoubtedly one of the greatest mysteries in the history of modern aviation.

Combining intimate prose with photographs, Ghost Guessed examines the after-effects of these unfortunate incidents. It looks through the multiple emotional strategies people employ to process absence caused by death in an era of high-tech visual media; images here are seen operating both as a means to validate facts and as cradles of comfort insulated from pain and self-delusion. Three chapters divided in subsections arrange the project chronologically. ‘Vanish’ awakens memories of the two accidents, their media coverage and impact; ‘Search’ focuses on the narrator’s failed attempt to reconnect with his family through an unsuccessful return to the crash site; and ‘Return’ is a flashback to a trip to Kuala Lumpur, presumably three weeks after the news of MH370 broke.

Ghost Guessed adds up to an alluring fictional essay on the visual culture with which Griggs and Kwiatwowski grew up. Long passages of text alternate loosely with a variety of registers that encompass the visual archaeology of the last 30 years: Family photographs, stills extracted from home videos, forensic reports from the crash scene, press images, TV screens and aerial photography offer one level of imagery, in tandem with the authors’ own photographs or digital collages. On the one hand they set the tone for dealing with demise and pain, but at the same time, they address how media – from domestic video cameras to today’s online streaming – have been paramount in creating our rational and metaphysical understanding of the self and the exterior world.

Read more

Ongoing digitisation and its intrinsic technological and aesthetic modes have been at the core of the skilful intertextual construction of Ghost Guessed. What began as a sporadic Skype correspondence between the two artists turned into a poignant co-authored memoir of life interconnections and synchronicities. The revelation of Andrew Lindberg’s accident during the conversations provided the breakthrough from theory to life, triggering a series of strange coincidences and life experiences, such as an unexpected opportunity for Griggs to undertake a trip to Malaysia, and his decision to revisit the crash recovery scene. Project and life started to collide.

Ghost Guessed eloquently addresses the pronounced shift of our times from the zapping condition, where screen and spectator are still physically and ontologically separated, to a form of second life, where orchestrated reality literally takes over. As early as the eighties, Andrew Lindberg’s grandfather is the first of the family to step into an alternative reality. Enclosed in a flight simulator during an aviation convention, he manages to channel his frustrated dreams of becoming a pilot without any risk of failure. Later, it is the narrator who undertakes the same route as the MH370. Surrounded by a screen in a controlled airspace chamber at Pavillon, one of Kuala Lumpur’s most popular shopping centres, he is able to position the aircraft safely back on the runway, rewriting history and restoring hope. If simulators perform it explicitly, this euphoric re-enactment of fate implicitly undercuts the whole Ghost Guessed. In order to make sense of reality’s haphazard and heavy events, the protagonists resort to social networks, snapshots and amateur video cameras –‘their eyes wandering non-stop through floods of images’. Eventually what is real has to take place in the realm of the virtual.

And yet the very thing that gives the overall narrative its linchpin is that which is impossible to reach. ‘Located deep within the wilderness of the White Earth Indian Reservation’, the event has not been recorded. The day Andrew’s body is recovered the gathered family is not allowed access to it. The body cannot be seen; no image is produced. ‘Years later, on the drive to return to the crash site, the narrator is lost and unable to make the photograph. By the time he is almost there, it is too dark’. Arriving at the scene neither ensures the success of the experience nor does it make him feel closer to his family. Ghost Guessed deals with this paradox – the excruciating albeit redemptive resistance of the fact. In the aftermath of the accident, the narrator, ‘floating through time with no structure’, appears watching for hours the lives of family and friends through social media. There is always the screen mediating, as if the relieving pure truth lay unreachable in the blind algorithmic parts of the simulation cabin.

In her video essay In Free Fall (2010), Hito Steyerl examines how the paradigm of linear perspective today is currently supplemented by groundless vertical perspective. Likewise, Ghost Guessed is replete of ‘vertical cities that measure the distance to the horizon in blocks’, and of views from above or towards the sky. This condition of verticality is even further accentuated towards the end of the book, pointing to the ultimate fragmentation of experience in a hyper-reality devoid of foundational schemes as Kuala Lumpur evokes a claustrophobic glass shimmering dreamscape. Under its discoloured sky, any sense of orientation is disrupted and multiplied into a million pieces. Even the views of Hawaii from the pilot’s cabin end up looking as a simulated landscape; the horizon is melting before our eyes.

‘Blue skies, clear skies, everything is ok’. A fascination with birds, flights, and clouds – both natural and virtual – too is vividly apparently in Ghost Guessed. Different cognitive systems, such as astrophysics, meteorology and religious omens, hint at solutions to enduring questions but these expectations crash against the narrative’s disquieting mix of conspiracy theories and endless media speculations. Extracted from video stills of jet flight crashes, the collage of the four planes in the middle of the book signals the mediatised hijacking explosions as it was exemplified in Johan Grimonprez’s glorious Dial History (1997). The sky is consolidated as the sanctuary of destruction where our more precious memories are anchored to impossible images. Up there, aside from the unlimited time of fall, there is no stable paradigm of orientation onto which we can hang. As Paul Virilio once remarked, each technology invents its own catastrophe, and with it a different celestial insurance. Ours is the permanent vertical fall.

Copyright: Natasha Christia/1000 Words 2018

James Pfaff. Alex & Me.1000 Words 23, Autumn issue 2016

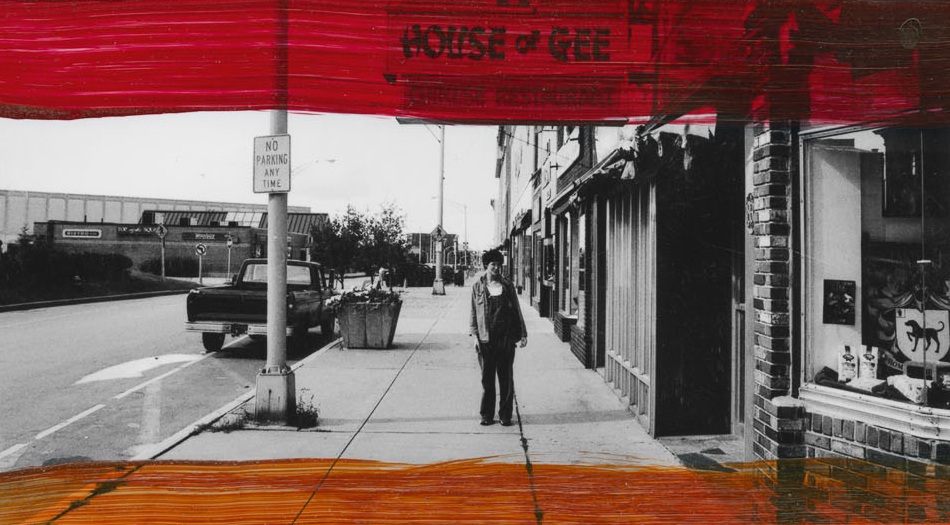

“Alex & Me” is an intimate autobiographical account of a road trip and a broken affair between a man and a woman. Materialised as a refreshingly original scrapbook with a strong diaristic scent, the project is the outcome of the creative tandem between the author of the pictures, Glasgow-based photographer James Pfaff, and two women; Francesca Seravalle, who curated the concept and sequence editing of the book, and Alex, the woman in the story. “Alex & Me” recovers out of Pfaff’s archive a series of photographs shot during the two-week car trip he and Alex took in September 1998 from Toronto to New Orleans and then back north to New York. The book carries the aura of a charmingly imperfect journal. It emerges as a container of elusive feelings that seek to accommodate themselves in the present, and is replete with a plethora of snapshots on the move. Car interiors, highways, gasoline stations, bars and telephone booths are all embedded alongside Alex’s vibrant portraits against the pages of a hand-painted journal tainted with expressive paintbrush strokes and handwritten texts.

Read more

Pfaff had originally conceived the idea for a publication back in 2007. However, his attempts had somehow not fallen into place. It was not until 2012, with Seravalle’s thought-provoking input, that “Alex & Me” took off as a diary emulating the aesthetic of a scrapbook. Seravalle encouraged Pfaff to harvest from his archives an assemblage of notebook pages and a cover originally made in 1998 but never intended for publication. The journal was completed with additional material originally shot during the journey and printed in local snappy snap shops along the way. Painting and texts came afterwards as a means for Pfaff to release his contemporary response to the work. Partially present in his anterior practice, painting served as the pretext for an artistically challenging process met at first with hesitation and then with more confidence. From a mere illustrative companion to the pictures, colour turned into an autonomous expressive element chronicling the dust and time of a journey past: white for the fences of the American houses, blue for the packaging of the cigarettes, red for the neon lights, and black for the highway darkness… The same applies to Pfaff’s evocative texts and poems. They could have been nothing but personal. This implication to all the aspects of the book renders it an authentic, quiet, albeit confident universe of words and images.

“Two books in one”, as Pfaff likes to describe it, “Alex & Me” is both a book and a memorial – a so to speak carrier of haunting experiences crystallised in images, colour strokes and words that claim for themselves a three-dimensional space the same way objects do. Similarly to Orhan Pamuk’s “Museum of Innocence” – a novel and a museum created simultaneously– it fulfils its mission as an iconographical depository of artefacts, scratches, clichés and Love; the print reproduction and the poem in the envelope that accompanies it confirm this worshipping penchant. With the pictures, painting and words articulated in first person, it reproduces Pfaff’s gaze, subjective response and passion. As such, it instigates an intuitive, heart-felt response from the viewer. No conceptual schemes are to be encountered here; just a cumulus of raw human experience alongside infinite stories of love, sorrow and solace to project and to narrate.

September 1998. In a parallel temporal dimension, we also found ourselves on the road. Likewise our trip was destined to turn into a catalyser of stormy inner changes in our timeline. We have however no material leftovers of these stories in our drawers. But somehow, Pfaff’s pictures succeed in filling the gap; gradually, they burrow into us as our most cherished souvenirs. They induce us to think of all those myriad insignificant incidents around the world that become unexpectedly symptomatic of the changes we are going through, and prepare us to confront larger issues. From today’s perspective, both Pfaff’s intimate fictions and ours seem to have unfolded when everything was about to change. Two years later, in September 2001, the new millennium affected abruptly History’s panorama, and to a great extent our faith towards Images and the way we perceived and consumed them. Something was irrevocably broken. America in September 1998 offers the set for a minor story with unexpected larger connotations, before the crashing and demolition of expectations and the beginning of a new era of neo-conservatism when the two protagonists of this story followed their own destinies and paths.

From the black and white sequences of its early pages to the subsequent double spreads in colour that intensify feeling and temporality, “Alex & Me” reveals itself as an open-ended artistic project that defies conventional progression. As if emanating from a Jim Jarmusch film, its neo-noir aesthetic makes a contained albeit heart-breaking allusion to Love without idolising or fetishizing it. It also establishes loose connections with “Double Mind: No Sex Last Night”, a 1992 film in which Sophie Calle and Greg Sephard, equipped with separate cameras, recorded every moment of their road trip across America. But whilst “Double Blind” finds its raison d’être in a voyeuristic tour-de-force operated by two antagonistic cameras within the confinement of its filmic time, here the weaving of relationships, desires and fears shifts outside narration and its historical time, in a continuous real-time narrative of a life shared and in a living book-object.

“Alex & Me” was conceived from its outset as an ever-expanding project made to be repainted, re-enacted and relived not only by Pfaff himself but by many others who have been actively involved in the reshaping of its story: his muse Alex (“everything comes out of me and her”), Seravalle (“the second woman who has scrutinised the project”), the audience, and, last but not least, the book which seems to claim its own life. The original scrapbook with Pfaff’s interventions was scanned and printed on a matt paper that would allow for further manipulation. During his public performances, Pfaff intervenes upon it anew with paint and words. He invests layers of his contemporary feelings onto a story in constant evolution and onto a book he describes as a “painful” one —“a book that took so long to make”, “a book with real consequences for peoples’ lives”. What’s more, an “unfinished book” marked by the sudden end of a friendship. Two years before its finalisation, Alex, his muse and creative companion in this sixteen-year endeavour suddenly stepped back. She asked him not to publish.

Pfaff’s story invokes the impossibility of letting go. It also speaks for the desperate attempt to hold on to what is relentlessly evaporating –that persistent memory that still haunts us as a ghostly manifestation of a past once lived. But it somehow manages to tackle it and make possible its reincarnation in the present without falling into banal melancholy. Beyond what a conventional solid (photo)book can represent, “Alex & Me” is a tangible performative capsule of memory. A cathartic meta-fictional experience in tenor, it opens up the possibility of alimenting, appropriating and recreating the past, while suggesting and acknowledging new collective modes in the creative process. “Alex & Me” has certainly become the path for Pfaff to look back over his story and deliver it to others. Now it is no longer just his; it is here for us to see and to react in our own way. And, perhaps this is where redemption is to be found in photography –even if only momentarily and restlessly.

Copyright: Natasha Christia/1000 Words 2016

Dragana Jurisic. My Own Unknown. 1000 Words 22, Spring issue 2016.

“André? André? … You will write a novel about me. I’m sure you will. Don’t say you won’t. Be careful: everything fades, everything vanishes. Something must remain of us…” (André Breton: Nadja, 1928, p. 100)

In 1954 a farm girl disappeared from a village in rural Yugoslavia. She supposedly left her husband to visit the doctor but never came back. Rumours speculate that she fled to Paris where she led a double life as a spy and a prostitute until her death in the 1980s. A colour photograph recovered from her few personal belongings portrays her striking a pose of a hypnotising albeit ambiguous charm: half-closed eyelids and mouth on the verge of pronouncing an inner score; a rose in her hand; next to her, a beast —its gleaming eyes and teeth destabilize the apparent harmony of the composition. Almost a century earlier, in Paris of the late 1880s, the body of a young anonymous woman was pulled out of the Seine River. Memorialised by her death mask, which became a popular morbid fixture in the years to come, her blossoming, breath-taking beauty was venerated by artists and writers, such as Man Ray, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Albert Camus, to name only a few.

Read more

These two female characters —the mysterious Mata Hari from the Cold War era Balkans, and the tragic figure of L’Inconnue de la Seine— are the protagonists of “My Own Unknown”, the latest project of Dublin-based artist Dragana Jurisic. A work in progress since 2014, “My Own Unknown” unfolds as a fascinating assemblage of five chapters that will eventually culminate into a fictionalised biography combining text and image. Here new and found photographs intermingle ruthlessly with notebook texts, video, performance, and diverse creative processes and voices. Hybrid and complex in tenor, “My Own Unknown” defies being classified as a conventional photo project. Its overlapping of languages, registers and dramatic motifs complies fully with the eclectic and expansive universe of Dragana Jurisic, the author behind it.

Jurisic is part photographer, part writer, part videographer, and all at the same time. In 2014 she came to international attention with “YU: The Lost Country”, an emotive, first person account of her return trip to former Yugoslavia after a decade of absence. Articulated as an installation and a book, the work draws upon the memories and aftereffects of war. It follows the pages of Rebecca West’s seminal travelogue “Black Lamb and Grey Falcon”, published in 1941, and Jurisic’s own visual and written recollections in the year 2011, 2012 and 2013. If “YU” concluded in a failure of self-recognition and national identification amidst a devastated landscape of rotten bonds and latent traumas, “My Own Unknown” unfolds as Jurisic’s most intimate autobiographical confession to date. Here the journey is accentuated. Departing from the tainted life of her aunt Gordana Čavić and the symbolic connotations of L’Inconnue de la Seine, it embraces an utterly personal tale that contemplates the turbulent fate of femininity and its quests within the stream of History and Art. The shades of the past, its intrigues, losses and ghosts, still cohabit the scenario here alongside a prevalent sense of lack of direction and a predominantly male historical narrative, wherein female characters exist as much as they are fetishised as sexually charged but otherwise “empty” objects.

Gordana Čavić and L’Inconnue de la Seine occupy respectively the two first chapters of “My Own Unknown”, but fuel the rest of the series giving birth to a chain of actions that deal with the attempt to make sense out of a whole of bits and parts. They place two mirrors for Jurisic’s own re-enactment of self in a triangle of female identity. Both are imagined rather than experienced the same way it occurs in André Breton’s autobiographical novel “Nadja” (1928) that chronicles his brief ten-day affair with an unknown woman. Nadja, the titular character in this key surrealist work, gains validity the moment she becomes approved by the author’s colleagues. As soon as Breton fixes her within his consciousness, he abandons her. Romance fades and Nadja is ultimately committed back to a sanatorium where she belongs. Jurisic’s female protagonists seem to fall in the same category. Both haunt the fantasies of others –Gordana is a sexual muse, whereas L’Inconnue the new Mona Lisa for artists. Like Nadja, they are not real persons but worshipped “souls in limbo” grounded in absence rather on historicity. The two first chapters of “My Own Unknown” perform this enchanted, androgynous gaze. They have to reference it, in order to finally overcome it and to unlock different registers. Unlike Breton’s, Jurisic’s fable soon reveals with bitter melancholy and resignation that the bottom line of the story is violence, cruelty and oppression. Moreover, it goes further to negotiate this ideal of female beauty, suggesting the possibility of a quiet historical reading of femininity far away from the noise of myth. In chapters 3 to 5, Gordana and L’Inconnue become the starting point of a subversive project executed by women and for women. The passive muse is resurrected as an active agent, unleashing a visual narrative of a different kind: the romantic fable gives its place to an anthropological, gender-directed iconographical tableau with clear political connotations.

In chapter, “100 Muses”, 100 women from Dublin, aged 18-85, responded to an open call to be photographed nude. Jurisic invited them indiscriminately to pose as one of the nine Muses of Antiquity, holding a replica of L’Inconnue mortuary mask and using the two following props: an old chair that looks like a throne, and a cheap curtain that potentially serves as a draping to cover the naked body. Upon completion of the shooting session, she conferred on them the opportunity to choose the portrait that represented them the most. Her intention was to empower her female sitters and to negotiate openly their relation with their bodies. The final portraits of these Deities of Fertility looking back at the camera possess a primitive, earthly beauty. Deprived by sexuality, their exposed bodies create a ritualistic amalgam that challenges iconographical clichés. They are physical manifestations and reinventions of the romantic ideal of the muse and by-products of the complicity between the author and her sitters. As such, they express the quest to detect a genuine female gaze and the freedom to accept one’s body within a society that carves out physical and mental standards for women. In chapter 4, “Her Mother and Her Daughters”, Jurisic proceeds to overlap the portraits of women who identified with the same muse, generating nine collective portraits. A stratigraphy of all the over-layered portraits gives as a result Mnemosyne, the daughter of Gaia and mother of the Nine Muses. A synthesized phantasmal taxidermy of skin and visages, the image of “The Mother” is the overlap of all. It condenses the maturity of different lives and skins, against the weight of immortality and idealization.

“Don’t’ be afraid to look into a shadow”, the fifth chapter of “My Own Unknown”, takes the viewer into a further remixing of female identity as a renewed collective meta-fiction. A video wraps and puts in motion the stories of all these women, with Jurisic placing herself in front of the camera. Here, her identification with her aunt Gordana Čavić is crystallized. They share, in her words, the same taste for adventure and braveness; they also share the awareness of an innocence lost in the depths of a river. Jurisic used the super-8 camera her aunt left behind to re-enact a life that was censored. The viewer is asked to access these short films through the holes of a series of black boxes. It is hard not to detect parallels between this diorama-like assemblage and Marcel Duchamp’s major artwork “Étant Données”. An unexpected and unimaginable landscape, visible only through the peepholes, communicates an intense experience of accessing a life shred in mystery, but imagined this time by women. In these rolls of film, woman emerges as the “other” — that which cannot be grasped, comprehended or penetrated, but only felt and sensed, the same way as war, displacement and tragedy. If male identity by norm operates as a solid narrative object (an object that is what it is, according to Sartre’s definition”), “My Own Unknown” looks back at femininity as a restless object that imaginatively allows the space for an ultimate unearthing of micro-histories of females that were abridged and buried in the tomb of History.

“Who am I?” asks the narrator voice in “Nadja”. “How well do we know ourselves? How well do we know the others?” asks Jurisic. She describes “My Own Unknown” as an existential attempt of self-knowledge, the only worthy enterprise amidst a world of disintegration and spiral events.

Her interpretation of history through individual identity and genre makes connections between beauty, understood as authenticity, and artistic endeavour. She evokes John Keats’ “Beauty is truth, truth beauty —that is all ye know on earth and all ye need to know”. But perhaps, rather than this deeply conflictive aesthetic-moral coupling of beauty and truth, Breton’s “convulsive beauty” provides a much more insightful term when it comes to highlighting the worshipping of images in her tale. “Beauty will be CONVULSIVE or will not be at all”. Convulsive beauty like History itself; sheer, hazardous and frenzied, like its search and quest for answers. In its indecisiveness of format and constant mutation, “My Own Unknown” seems to reproduce the liquid, non-linear identity of its women protagonists. There is something ungraspable, anarchic and stormy in its multiplicity of chapters, installations and Jurisic’s proper notebooks that will bring as their final outcome the fictionalised photography-embedded autobiography of her aunt and L’Inconnue. Set against the milky surface of River Seine, archival photographs, recollections, fictions and documents add more to the mystery to a formidable woman who “is not going back —will never go back there”… For once more, “Nadja” provides a striking parallel. As counterparts in time of male and female writing, the two artworks form part of the same Sebaldian legacy of oeuvres that integrate images into their first-person narrative.

As vessels that communicate with each other, the chapters, processes and distinct authorial voices of “My Own Unknown” keep the viewer traveling. Its female muses emerge like shades against a veiled backdrop. Pulled ashore from a river of mystery, they regain life. When not covered by a mask, their gazes are firmly addressed towards the camera. And yet, despite their urge to overcome vulnerability, they slip once more into a tranquil death in the area of meaning. There is so much of sadness and latent resignation infusing these bodies. There is an awareness of futility amidst our turbulent, disappearing times. There is the acknowledgment that recession into absence is the final redemption. Bodies are deemed to vanish, to fade…

By the moment I complete the reading of Jurisic’s notebooks, Maurice Blanchot’s account of L’Inconnue resonates in my ears:

“A young girl with closed eyes, enlivened by a smile so relaxed and at ease… that one could have believed that she drowned in an instant of extreme happiness”.

And so the story continues.

Copyright: Natasha Christia/1000 Words 2016

Vittorio Mortarotti. The First Day of Good Weather.1000 Words 21, Winter issue 2016.

Impelled by a similar penchant, Mortarotti’s narrative takes me through a misty topography of devastation, melancholy and resignation. Nothing in it appears particularly visible or obvious. There is a bluish undertone in the whole book –a sort of mute score reverberating in the depths of an ocean. Night and day alternate indifferently in perennial circles of rising tides; views of semi-demolished houses, cracked cement blocks and smashed cars are paired up with flashy portraits of drained individuals and tormented night bar affairs. And yet, I can tell that beneath this rough silent mood there is a winding stream of emotions, a lust to hang on to life. This collision of distinctive visual and emotional registers within a low-spirited, obscure and industrialized nature turns into a both graphic and literal incarnation of an attempt to get access to a secret, to recollect its traces, to finally grasp how life can be after everything has been smashed into a million pieces.

Then, all of a sudden, in the middle of the book, a text insert dating back to May 1999 appears. It is a letter written in French by a Japanese woman named Kaori and addressed to a man. This letter adds up a literal complexity to the story. It makes clear that there is much more in here –something deep, personal and intimate.

Read more

the pages to follow, the story recovers its visual pace. While Mortarotti’s gaze keeps safeguarding its distance from dramatic exasperations, it unleashes an unsettling emotional and existential register that drives me away from the letter and away from words.

And so it goes… In the colophon I read that the book brings together three unconnected moments: the fall of the atomic bomb over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, the death of Mortarotti’s own father and teen-aged brother in a car accident on July 8-9, 1999, and the terrible earthquake and Tsunami that shook Japan in March 2011. All moments of historical relevancy; all massive, unexpected, unprecedented and utterly absurd in their after-effects.

In the wake of this data assemblage, everything falls into place. Death appears here with capital letters and History intermingles with personal traumas. The locations shown in the book recover their names: Fukushima, Tokyo, Hiroshima … As far as the letter is concerned, it forms part of the correspondence between Mortarotti’s brother and Kaori, his Japanese girlfriend who kept on writing and sending postcards for months after the accident. Tracking this pack of letters and looking for the woman fifteen years later became for Mortarotti a pretext to visit Fukushima and the area hit by the Tsunami in a cathartic search of what might have been the aftermath of stories of loss other than his own.

I am aware now of many key elements of the story. Too many probably in the eyes of the purists still inhabiting our photographic community. Photographic purism would dismiss the book I hold in my hands as too dependent on words. Photographic purism would dictate that sequence has to speak for itself: We do not need illuminating words; when these are needed, it is because images do not work for themselves. All this, as if proclaiming the autonomy of the Image from the Word, would confer it with the ultimate credibility status…

Curiously, to me, “The First Day of Good Weather” feels relevant precisely because of its “contaminated” versatile mood. Delimitating visual storytelling or photobook-making to a pure form is an option in its own right. Nevertheless, it cannot be axiomatic. It does not and should not exclude other options. As Jean-Luc Godard would put it, “It’s not where you take things from — it’s where you take them to”.

“The First Day of Good Weather” is a hybrid photobook in every sense of the word. By expanding its branches on apparently irrelevant storylines, its narrative adopts an elliptic style akin to cinema and literature. At the same time, it masterfully combines and balances the documentary, diaristic and conceptual modes with a marked preference for a “slow” inception of reality and its facts. The links between the photographer’s personal tragedy and Japan’s collective trauma play out the universal mechanisms of coping with grief and moving on after experiencing a dramatic event. Mortarotti manages to tackle the delicate and private sphere of mourning without falling into clichés or to an excess of autobiographical references. What’s more, he brings Japan to the foreground in an unpretentious and neutral way. It would have been easy to let it take up the entire frame for the umpteenth time, but he does not. He avoids temptations.

How can we approach an alien space? How can we cope with death and its remnants? How can we overcome it? The components of Mortarotti’s story are tied together by the intuitive assumption that the bits and pieces of our immense world are interconnected. During most of his journey around Japan, we feel attached to the ground. Then the bird’s-eye view in the small postcard pictures of skyscrapers and the portrait of the woman (Kaori in the present) against the window and the blue sky introduce a soft airy element –a parallel dimension to this journey. There is a climax of sensations that reinforces an awareness of the randomness of cosmic events –a volatile lightness horrendous in many ways, as the title of the project suggests: The first day of good weather was the day life stopped in Hiroshima. “The first day of good weather” was the order issued by President Truman to drop the atomic bomb on Japan. On August 6, 1945, it was raining over the other targets. It was sunny in Hiroshima.

We are used to conceive books –not merely photobooks– as static objects, but perhaps it would be useful to start thinking that they are not. Books are elastic condensers of time. They exist in time; they grow up with us. They stand for a sort of synesthetic experience where we, the readers-viewers, have to contribute our imagination and intuition to fill in the gaps.

So I let myself drift into “The First Day of Good Weather”.

I let myself add to its sequence layers of experience emanating from my personal debris. Experience that, rather than explaining, adds more lines to the story as if it were an unfinished novel. I catch myself going back and forth. Especially backwards, to be frank, in a futile hope that this movement could restore something past; rather than revoking the trauma, I seek to accommodate it the present. I catch myself returning to “The First Day of Good Weather” for there is something in it that persistently resonates in my mind: an intense, sustained and profound force that replenishes its argument and makes me see it anew.

Copyright: Natasha Christia/1000 Words 2016

On devastation and other stories. An entry for Photocaptionist on Regine Petersen. Photocaptionist, fall 2015.

How are we to deal with the collision of images and text in the work of Regine Petersen? For it is a collision, a deliberate one. When compiling data for the essay accompanying “Find a Fallen Star”, I found myself exploring the interweaving of pictures and the written word. A double equation at work emerged before my eyes: Texts therein operated like visual unities as much as images were equivalent to language blocks. Petersen instigates this sort of dialectic coupling. The visual material she employs (be it archival resources or her own photographs) is not meant as a plain illustration of the texts she cites, neither the other way round. There is no intention of doing so whatsoever. It rather serves as a disquieting counterpoint that renders meaning milky and sub-aqueous. In its semantic richness, meaning expands amidst an automatic writing on random occurrences and their unpredictable outcomes to human fate.

Read more

The Tunguska incident showcased in this entry conforms an imaginary blank chapter of “Find a Fallen Star”. It is a variant albeit not a less significant case in Petersen’s relentlessly expanding archive on meteorites. On June 30 1908, just after seven in the morning, an explosion took place over the Siberian Taiga. It is believed to have originated from an incoming comet or asteroid that produced an airburst of five to ten kilometres above the earth’s surface without actually hitting it. Despite the fact that the blast centre was remote and uninhabited, people felt the shockwave within forty miles from ground zero. The explosion reverberated in illuminated skies visible to distant areas of the world. It knocked down about eighty million Taiga trees over an area of 2,000 square kilometres and killed hundreds of reindeer. Its energy was estimated about 1,000 times greater than that of the Hiroshima bomb. No impact crater was found

Contrarily to the three chapters of “Find a Fallen Star” (“Stars fell on Alabama”, “Fragments” and “The Indian Iron”), wherein the irruption of meteorites to earth gives rise to a chain of relatively un-dramatic, non-sensational events, the Tunguska case is a hazardous tale of destruction. And yet, here, the piece of cosmic stone that once struck through the atmosphere provoking environmental disaster on an unforeseen scale is up to this day evinced as a non-witnessed and non-tangible forensic record, relegated to the realm of speculation. What remains is the blast that Petersen literally enacts in the semantic clash of images and texts. In their openness, images and texts turn into indexical containers of concocted suppositions and ghostly stories in need of decoding. They wind and connect from one pairing to the other, exercising a quasi-physical impact on us. The rest is History and Myth.

While conducting research on the origins of the Tunguska explosion, I stumbled upon a handful of scientific and other fabulous conspiracy theories, ranging from Nikola Tesla’s experiments with wireless transmission to UFOs or mosquito explosions. Petersen’s approach performs how this information noise collides with the object that remains miraculously absent. Incomprehensible, ungraspable, the object is replaced and transformed into something else. A sort of visual pastiche conjectures a disparate global whole that paradoxically mends up to the Tunguska reality: Tree rings, illuminated skies, a little graphic of the blast with a schematized bird’s view of flattened trees as well as different told and re-told perspectives of its destructive power (by foreigners or the local Evenki people). All these visual and textual testimonies move along a line of long vs. short exposures and cosmic vs. mundane temporalities, conforming an enthralling narrative sequence on minorities, lost words and eclipsed cultures.

Weaving in and out of facts, photography has this inexplicable side effect of absurd meaninglessness. Rather than filling the holes, it opens new ones. While its natural inclination is to provide a perspective of the past, it exposes the anomalies of interpretation and what is simply out of reach as if offering redemption to the phantoms generated in our times from time immemorial. It seems to me that beyond all beauty and catastrophe, ultimately there is nothing but the physical exhaustion of images. And devastation, mute devastation in the spirit that W.G. Sebald once described it in The Rings of Saturn:

“Where a short while ago the dawn chorus had at times reached such a pitch that we had to close the bedroom windows, where larks had risen on the morning air above the fields and where, in the evenings, we occasionally even heard a nightingale in the thicket, its pure and penetrating song punctuated by theatrical silences, there was now not a living sound”.[1]

[1] SEBALD, W.G., The Rings of Saturn. Vintage Books: London, 2002, p. 268.

Copyright: Natasha Christia/Photocaptionist, 2015

“Find a Fallen Star”. Essay for Regine Petersen: Find a Fallen Star. Kehrer Verlag, 2015.

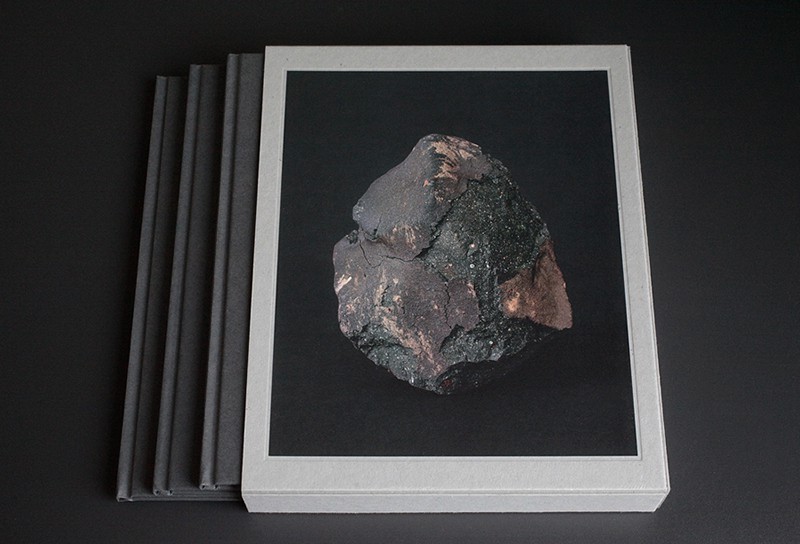

Regine Petersen employs meteorite falls to venture into her multi-layered narratives. Her practice is based on a seemingly straightforward investigation that employs occurrence as a pretext for further research. Petersen visits places where meteorite incidents have been recorded, interviews witnesses and gathers all relevant forensic evidence –archive press cuttings, testimony transcripts, religious and literary fragments, genealogy records and found images. In the resulting final narrative, this extensive bulk of visual and textual information is reworked in tandem with her own fieldwork and innate sensibilities into a fascinating whole.

Though the background of the three stories in “Find a Fallen Star” is different, though their action takes place in three geographically and culturally disparate areas of the world, they all form consecutive chapters of the same multi-fold approach. They are tied into a powerful and dense semantic threshold, whose main quest is reinforcing an insightful exploration of the potential abilities of the image to both sustain and challenge its proper core foundation; myth. What follows are the ingredients omnipresent in any melodrama: proximity and distance, the lapses and decays of memory, the mundane and the sublime, and, of course, as it is to be expected in any occurrence of cosmic character, the universe with its infinite intergalactic and interstellar constellations.

The meteorite in itself, always the meteorite, this ancient pearl of the universe condensing on its surface billions of kilometres, billions of years. The meteorite, a heavenly sign of awe-inspiring divine dimensions and an artefact of ruthless scientific observation, triggers spiritual amazement but can also instigate fear, destruction and flames. From time to time it becomes an intruder to human history; it just streaks through the atmosphere and falls on the earth, interrupting everyday life, dismantling individual and collective fate and unravelling a handful of monetary transactions, museum donations, and small private dramas

Read more

1954: In Sylacauga, Ann Elizabeth Hodges, a thirty-four year old woman is struck by an unidentified grapefruit-shaped object while napping on the couch of her living room. She is the first recorded human subject ever to have been injured by a meteorite. Her featuring on the CBS panel game show “I’ve got a secret” in the aftermath of this absurd event encompasses the bliss and the fall of a fading star. Manifested as a huge bruise on her hip, the abrupt collision of universe’s forces onto her body takes only four minutes to be consumed by media frenzy. The day after the fall, Julius McKinney, an Afro-American farmer, finds a second smaller fragment of the same meteorite that hit Ann Hodges but in contrast to her, keeps his discovery secret for some time, probably out of fear that it will be confiscated. Later on he sells the stone for profit. 1958: A meteorite falls in Ramsdorf, a small town in German Westphalia, unearthing a torment of hidden tensions and authority issues in the local community, and putting into test its apparently peaceful coexistence and human relationships. A group of children discovers it and breaks it in five pieces. Then the village doctor intervenes, the extra-terrestrial object’s fragments are reunited and a contract is signed, according to which they come into his possession for 10 DM each. 2006: A much less spectacular encounter of a meteorite with humans happens in India. A meteorite falls at Kanwarpura village near Rawatbhata, where the Rajasthan Atomic Power Plant is situated. The two shepherds who come across it are nomads who, just like the stone, stand outside the realm of History. They enter the stage as long as it takes them to discover it, drag it for some distance, immerse it in water, report it to local authorities, and then leave. What is left behind are politics, speculation and a huge piece of iron junk.

On Personal Memory, Myth and Language

“This then, I thought, as I looked round about me, is the representation of history. It requires a falsification of perspective. We, the survivors, see everything from above, see everything at once, and still we do not know how it was.

W. G. Sebald: The Rings of Saturn [1]

The irruption of meteorites into the flow of History triggers an infinite number of accounts that confront the finite nature of human perception with the infinity of the universe. “Find a Fallen Star” reverberates through its aesthetics the collision of meteorites with the earth. It performs it in all its absurdity by means of a collision of images and words and the semantic pitfalls the latter causes. The three episodes featured here are packed with a continuum of factual evidence of various kinds: reports facilitated by police authorities, lawsuit documents over property, contracts, a newspaper article on Petersen herself, Internet forum–posts of meteorite enthusiasts and, last but not least, press images and found photographs. All machine-typed in a bureaucratic way, all approved by investigation committees and experts, their mission is to shed light on facts, yet obstruct it instead. Fitting chaos into the human scale is not an easy business.

Interviews work as a substantial tool to this frenetic enquiry for facts. The Alabama chapter includes a later interview recording that finds Eugene Hodges, Ann’s husband, some five decades after the events. A key figure but also a very conflictive agent in the story, Eugene is supposed to have been ill-tempered in the past, but now is mellow and less resolute when recollecting the events of the fall and when defending his version about the dispute over possession and his divorce. In his early nineties, he has partially lost the capacity of remembering and/or disremembering, putting at stake the interviewers’ attempt to extract from their encounter a vivacious account of what really happened in Sylacauga. As his version of the story unfolds through his old fragile southern accent, Ann Elizabeth Hodges gets more and more blurry. Her figure is gradually disappearing; we cannot tell who she is and whether her fate was tragic or not.

This sort of oral recollections, plethoric and abundant in style, albeit unable to clear the path to information, are even more present in “Fragments”, the Ramsdorf chapter. Some sixty years later, conversation still makes itself omnipresent here through the disparate testimonies of some of the children (now adults) who were supposed to have been made privy to the incident. Ferdinand, Luise, Willi, Horst, Ludger, Hildegard, Gisela, Oswald, Reinhard… Each one of them provides the artist with their own version of the facts. All of them safeguard a valuable part of the truth. Theirs. They took it with them when breaking the meteorite in five pieces. This is the way life-stories are constructed; people learn them by heart, they employ them as shields in order to sustain their identity, they become them. Putting together the fragments that perfectly match each other makes it possible to re-establish the original shape of the meteorite, but this does not happen with the scattered bits of memory. As always, there is a voice missing: Franz, one of the main incident witnesses, is not alive to recount his version. As in the conjured fields of Alabama, here too people who are no longer present take their words with them.

In “The Indian Iron”, language throws an opaque veil on testimonies blurring the horizon. The interview with the villagers of Kanwarpura is purposely left in its original version –Hadoti dialect mixed with Petersen’s original questions in English. In contrast with the almost repressive language of “Fragments”, translation does not seem to work properly here. Lines and lines of the Rajasthani conversation are resumed in short answer phrases that do not address the original questions. Many essential pieces of information seem to escape, at least to non-Hadoti speakers. Petersen deliberately reproduces her experience while conducting research in India –the experience of being marginalised from the dissemination of meaning. And yet, these leftovers of meaning –whole blocks of Devanagari letters occupying the sequence– suddenly allow a novel space for the standpoint of the “Other”. They conduct an enquiry through the perception of other people and cultures, thus releasing the monolithic westernised condition of the previous two chapters. History can be written in many ways by many hands, suggests Petersen. Sometimes truth seems to lie in the gaps and lapses of language, somewhere in between words and on the other side of representation; it can be even found outside Myth and also outside the semantic trappings of the image, as we are about to see…

On a Dialectical Image

“The essence, properly speaking of the image, and very particularly of the photo, is to be found in that power of appearance that cannot be explained by the representational content”.

François Laruelle: The Concept Non-Photography [2]

Petersen treats text as a surface, as a meta-form that expands into space and is perceived in terms of its property of representation rather than as writing. It is not words and arguments per se that matter to her but the experience of proximity and/or distance with facts they convey as interchangeable variables of fantasy. As a mental constellation of this physically sensed condition of aloofness, language also suggests a way to delve into her still contemplative images. “Find a Fallen Star” is replete with visual equations of proximity and farness. The camera constantly re-enacts on many levels the experience of micro and macro scale in the natural world. It records creatures barely perceptible to the eye. Besides the imprint they leave on the environment, creatures such as a frog, a chameleon, a snake on the path, a donkey or merely an egg on the ground, are minor cosmic components, epiphanies of fragility and humble reminders of the limitation of perception. Other kinds of images, as the Google view of a crater in India, aerial views or amateur astronomer takes of a moon eclipse, appear as minimising the dramatic effect of human presence amidst the vast cosmos, while performing the earthly necessity to catalogue and possess the world, to literally fit it within science and the confined limits of myth. As a whole, these visual haikus can be seen as symbolising the material distances meteorites cross, the miles the artist herself had to cover in order to gain access to geographically remote areas of India or the American South. But, ultimately, they also seem to imply how troublesome the path to meaning and interpretation is.

Texts and images turn into integral elements of the selection and spatial organisation of information in “Find a Fallen Star”. They engage in cross-temporal conversations, exposing the unbearable lightness of understanding in a fragmented world. By doing so, they involuntarily twist documentary photography’s traditional exclamations of the sort “If you aren’t good enough, you are not close enough” (Robert Capa). It goes without saying that in a media and communication era Petersen feels that she cannot nor has to be close. Concerned with the aftermath, her photography maps the world in its chaotic incompleteness. Petersen goes to the impact sites after events have happened and sees what is left. Her practice is not premeditated. She recollects photographs from the surface, allowing margin for chance. Her pictures, despite their registering character, are not mere images of material remains. Motivated by an intuitive and curious approach to the world and by a desire to make connections, they are articulated as independent visual unities leading to insightful metaphoric associations. They turn into liquid images that, depending on their context, meld the signifier and the signified into a third object, too subtle to openly spell its connections.

Take meteorites, for example. They work here both as real tangible rocks and as mental images binding form, language and content in an array of rich dialectic associations. Like photographs, they are representations and re-presentations, triggering a series of metaphors in relation to memory, tangibility and materiality. They simultaneously show and conceal. Meteorites may contain unbiased records of ancient memory in their interior, but we cannot obtain real access to this cosmic information; we can only imagine and project it. Then unexpectedly, these dreamlike apparitions of the sky reach our hand as artefacts in museum captivity. Petersen takes time to photograph them as isolated still lifes against a black background. Realised in large-format and with long exposures, their photographs transmit a feeling that is by turns sensational and unsensational. On the one hand, they advocate the miracle of bearing witness to an object with evident religious and sacral connotations, or, alternatively, a luxury item. On the other hand, one cannot let go that each of these images is nothing but the record of a banal rock. Here is before us, a single piece of stone unleashing a handful of absurd stories.

Likewise, chimps –a recurrent motif in “Find a Fallen Star– are activated on a second-order speech level that abandons the field of literacy for the sake of some magical thinking. Monkeys are a part of the natural wonder. They live in a world of their own that we cannot access, but at the same time their genealogy is related with our past. Monkeys also carry mythical connotations; they are parts of a colourful ritual that contrasts with German small-town Catholicism as implied in “Fragments”. They are the “Gods of the Old World”, worshipped as non-figurative rectangular objects embellished with rice and coconut. In the recent past, they formed the International Space Hall of Fame. They were sent to space, and the empty space suits of those who made it back are exhibited as emblems of human ambition and journey exploration. But Petersen’s eloquent visual narrative undermines such an iconic reading, pinpointing what these animals really are: namely, involuntarily launched bodies to an extra-terrestrial orbit of perils. As if thinking could be performed in their portraits, history and reality find their expression in the experience of absolute terror and fear these poor chimps must have experienced during their historic missions.

On Melodrama and, finally, on Facts

Although “Find a Fallen Star” unfolds as a threefold narrative, the leitmotif behind it is one and the same. It is all about a melodrama palpitating with passion, counter-memory and exhaustion –a melodrama that sardonically cuts through religion, politics and collective fantasy. Its three acts are orchestrated as cyclical narratives of beguiling and tantalising polarities that can be read in one way or the other. As unpredictable outsiders, meteorites invade the stage and become masterfully interwoven with the extremities of life. Experiences and history become cognisable and visible through them. In a transformative sense, they confront us with multiple perspectives and entombed secrets. At the outset of each tale there is a mystical, supernatural hint, as if the answer to everything were to be found in allusions to the Lord and in Judgment Day. But, paradoxically, what ultimately prevails are the subterranean forces of human relations taking over and raw facts.

“Stars fell on Alabama” takes off as a white woman’s tale. It transports us to the mid-fifties’ American South, while eloquently describing the way Ann Hodges’ quotidian life becomes afflicted from the media attention and legal disputes over possession that accompany her encounter with the extra-terrestrial. Then, when less expected, the narrative suddenly becomes engaged with the ventures of Julius McKinney, a 60 year-old black farmer who happens to discover another piece of the rock from outer space in the middle of a dirt road. First we see him in a contemporary newspaper photograph surrounded by his family, his hands holding the “black coloured pearl”. Then, looking back, the original negative is restored, demonstrating that part of the frame of the reproduced image had been over-painted to hide the extreme poverty of the McKinney family. Narrative is moved from the context of American nostalgia to the dark fringes of old plantation days. We find ourselves before a second invisible and less idealised level of reading that addresses altogether the issue of racial segregation while showcasing a whole draft of contradictions and anomalies in the construction of the photographic image. The flow of images takes us even further, into a realm where polarities melt into one. During her research, Petersen discovers in the genealogical tree of the McKinneys the complex African-Scottish origins of their ancestors: Julius McKinney’s father was the fruit of a relation between a white slave owner and a slave, following a series of biracial relationships. She thus deciphers the story of a white man within a black man the same way a careful viewer will spot a little Americana statue in the desolating opening portrait of Ann Hodges, next to her radio. In the end, things are not what they appear at first sight. We can never fully know the grim undercurrents of history that lie in store or its unexpected and surprising twists that bring the opposites closer. And so the story unfolds, unexpected, ambiguous and random. Its two narrative threads are masterfully tied together as one through the religious texts that open and close the chapter respectively. The comments of Mormon prophet Joseph Smith about the stellar shower of 1833 in Alabama are paired with the recollections of Amanda Young, a slave, on Judgment Day, punishment and redemption. Beyond specific statements on contemporary racial injustices and minorities, the “black pearl” ends up performing altogether the inherent dynamics of the place it falls on, even if this is by chance.

As Petersen wistfully states, “Places do not change much. Only life on top of them does”. Beneath the surface of her imagery lies tension. In “Stars fall on Alabama”, everything feels just different. There is a poetic connection with the muddy earth, the blood-coloured moon and the pine trees in these pictures –a so to speak dramatic, cinematic-like feeling transcribing the savage magical spell of Carl Carmer’s Alabama into a universe of stillness [3]. In “Fragments”, the presence of this ambiguous world brooding under the surface is further reinforced. Ramsdorf seems like a fragmented world of powerful father figures (the doctor) and the surrogates for them (the male children). All of them carry an impending need to impose their proper views, to become comprehended and appreciated. Regardless of their flaws and possible fallibility of memory, they are human beings thwarted by individual limitations and the circumstantial historical stances of society. And yet, beyond them, there is always a broader historical context to bear in mind. If in the Sylacauga tale the hidden agenda is racial segregation, here it is post-war Germany in the shadow of its recent past. In their sculptural-like quality, images such as “Mole hills” draw allegorically this two-fold hidden past wounding under the earth, whereas the Wehrmacht steel helmet at the village church made into a picking bag shows the very same past palpitating in actuality. There is a sort of autobiographical element in this chapter, a feeling of estrangement Petersen feels at times, when investigating about her own country, an inability to fully recognise herself in the repressive language of German sermon post-war articles. This feeling of alienation is perpetuated in the other series; it serves as a reminder of what-has-been by locating the remaining traces of what is past in the contemporary world. Take, for example, the portrait of Wernher von Braun, an ex-Nazi technician who became member of the NASA crew, in the Alabama chapter.

As soon as the curtain of history unfolds, we are made privy to a Cold-War-era feeling that dictates the underlying historical context and mood of Petersen’s stories. In “Fragments”, the anonymous photograph of the boy building his Sputnik out of a milk can is a direct allusion to the same space dream with that of the NASA chimpanzees in Alabama. As far as “The Indian Iron” is concerned, it commences as a 19th century tale with religious and colonial nuances. Like the previous chapters, it is gradually arising from amidst a legend to 2006. It somehow ends up being part of the same culture of globalisation, politics and war. The initial association of the meteorite with a Pakistani bombing or its quick dismissal by American meteorite enthusiasts as a piece of junk from the neighbouring power plant brings to our attention the current political patterns of the zone. For once more, Petersen’s narrative tells us something crucial about prejudices, localisms and the narrow focus of Westerners failing to see the broader scheme.